Amarnath Sehgal was a man of many moods as evidenced by his fearless art focused on Partition. In his centenary year, a museum dedicated to him and a book traces his illustrious career

Amarnath Sehgal was a man of many moods as evidenced by his fearless art focused on Partition. In his centenary year, a museum dedicated to him and a book traces his illustrious career

The year was 1945. Echoes of war slogans fueled unrest in the deepest trenches of then-undivided India. Two years later, Amarnath Sehgal’s family made their way from Lahore to the Kullu Valley, Himachal Pradesh, in search of opportunities offered by independent India.

Sehgal’s career, which spanned 60 years, made eventful detours through different continents, eventually ending in the studio in Delhi where he worked and lived.

After more than five years of renovations and collections, the studio which opened its doors as a museum in 2019 gives visitors a glimpse of Sehgal not only as an artist, but also as a person. And now a book titled 100 years of Sehgal accompanies this effort, marking the centenary of the artist.

A view of the museum | photo credit: special arrangement

When Mandira Rowe, the curator, was thrown into an already vast collection that was diverse in both medium and context, she admits she was overwhelmed. “I realized that it is the whole life of a person who is absorbed in one space. I decided that I needed to know more about that person to understand his art. My research began on how Who exactly was this person.” Bhandar is still a work in progress. In the course of their work, the team realized that a lot of Sehgal’s pieces in the country are spread across the Delhi-NCR region. Still looking for them.

Amarnath Sehgal was a man who wore his heart on his sleeve: hiding in his studio he would try to make sense of the rejections he faced. And through art, he bore the wounds of the horrors of Partition.

Be it through distorted faces that merge into a poignant mass of screams, sticking figures with their hands in protest or echoing sound waves frozen in motion, the artist did not hesitate to expose his mind. . His direct translation of emotion into tangible mediums such as bronze leaves the viewer with a powerful impression of man, even more than the artist.

Rebellion (1957) | photo credit: special arrangement

where does he live

Sehgal was born in a large family in 1922 at Campbelpur in Attock district of present-day Pakistan. Although an engineering student with an inclination towards physics, his love for art led him to enroll in the Mayo School of Art in pre-partition Pakistan and later found comfort in the conceptual space created by BC Sanyal (also his mentor): art The Lahore School.

It wasn’t too difficult to get to know him, says Mandira, “He put all his feelings into his sculptures, his feelings into his letters, and despair into his paintings. Through this process, I came to know that he He was a kind man, who was very sensitive indeed to a world like ours. But his sensitivity also made him fearless in expressing himself. You can see the drastic changes in his art before and after Partition.”

Mandira began with her letters, correspondence and poems, some of which were still drafts. Sehgal’s son, Rajan Sehgal, captures it well, “My father was like a kabaddi guy who never threw a single piece of paper. We already had such a rich collection.”

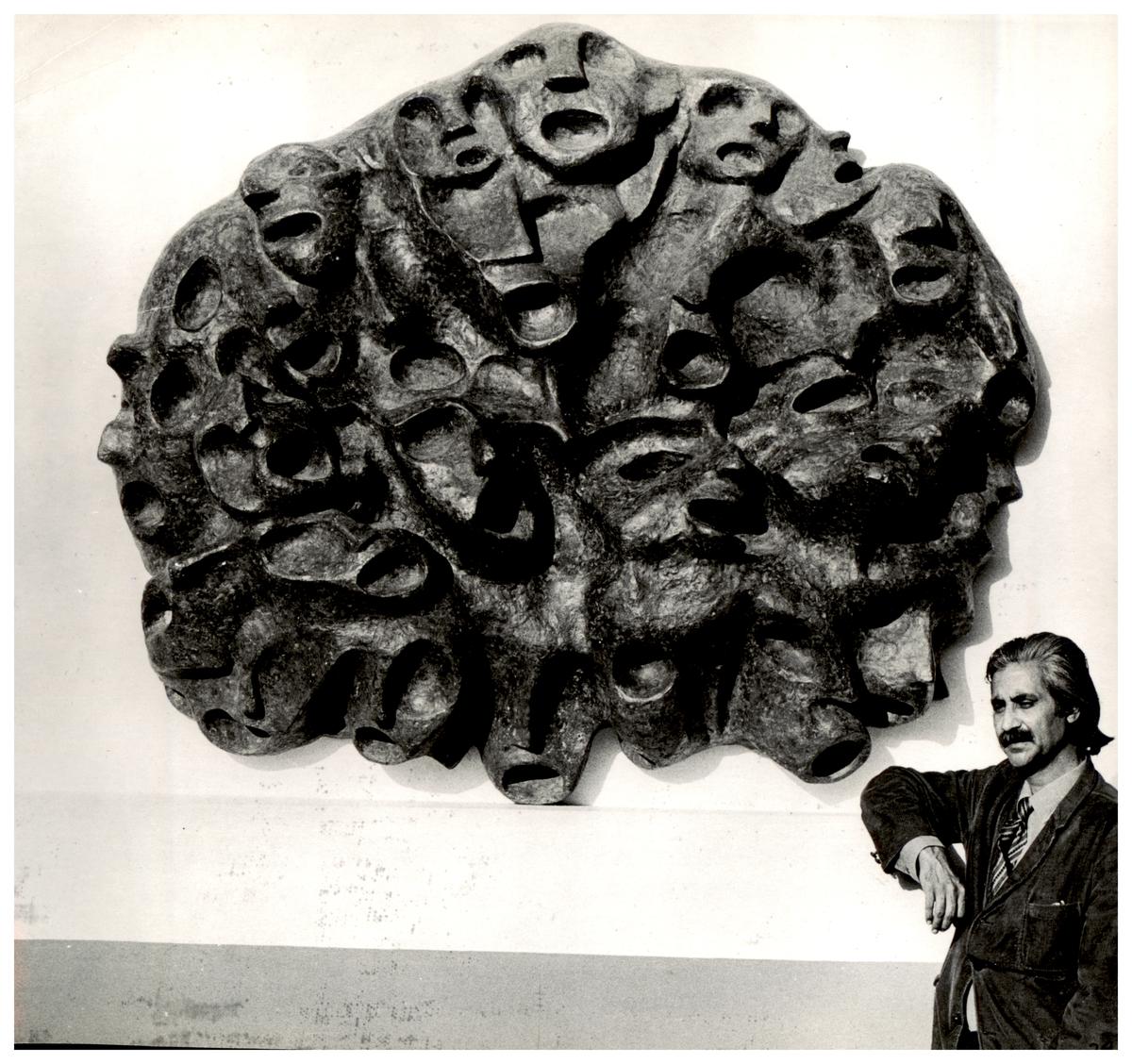

Sehgal with one of his most famous works, Anguished Cry (1971). photo credit: special arrangement

As indicated by his work, Sehgal was deeply influenced by wrongdoings in the world – be it wars, communal riots, religious inequalities or atrocities against women – and never shied away from expressing his opinion. Anguished Cries, one of his most famous sculptures (1971) is a shocking mix of screaming faces.

At the time, while most of his contemporaries stuck to traditional frames of landscape and scenery, Sehgal captured the agony, pain and improvisation in his compositions; Knowingly or unknowingly, there is a subtle message hidden in every action. Perhaps that is why he found a safe, encouraging place outside India in New York, where he went on scholarship, and then to his studio in Luxembourg.

“In his unpublished memoir, he writes that his faculty in New York was influenced by his behavior. He brought with him the concept of ‘master-disciple’, which prompted his faculty to lend him a studio to work in, says Mandira. He was in the East Village, which at the time (post-World War II America) was hosting a young yet thriving arts community. There he met Tony Smith. He and Smith, both broke up, would share a cup of tea and do several things. Artists and contemporaries such as Smith at the time, [Jackson] pollock and [Barnett] Newman used to help each other out by lending studios.”

It was here that Sehgal broke the shackles of the modern Bengal School of Drawing and opened his eyes to expressionism and abstraction. Pollock’s technique changed Sehgal’s view of public art, Mandira says.

Sehgal in his studio. photo credit: special arrangement

Sehgal, father

Although Sehgal was very forthright, Sehgal was a caring father. “When I was a kid, I remember doodling with him and playing with his tools. He never chased me away.” Rajan adds, “Coming back from school, we would see that he changed into his overalls and pajamas and went back to the studio. Raman [Sehgal] And I knew he was different. Over the years I got to know him more and more as an artist.” In the book, the two are reminiscent of his relationship with Segal, the studio, and Luxembourg.

Back at the museum located in Jangpura Extension, the physical display is divided into five levels, with various vantage points as per the artist’s wish. It sits on a plot of land gifted to Sehgal by the then prime minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru in 1964, says Rajan. The main space has a high ceiling which was set up keeping in mind the possibility of building a larger statue within the studio. Tapestries, hyenas, an oil painting, various mediums of his sculptures, and paper works appear in this intricately designed space.

Sehgal’s Rising Tide at Ford Foundation, New Delhi | photo credit: john rizwick

Rajan says that during the last few years of Sehgal’s life, the man got noticed from the studio. And as luck would have it, he breathed his last on December 10, 2007, at the same studio.

Mandira said that she did not intend to idolize him. “I want people to know more about him. He really has a life less known.”