As Mani Ratnam’s ‘Nayakan’ celebrates 35 years, architect Nandan Balsavar, who experienced the film set at the Venus Studio in Madras in 1987, understood some of its muted connotations.

As Mani Ratnam’s ‘Nayakan’ celebrates 35 years, architect Nandan Balsavar, who experienced the film set at the Venus Studio in Madras in 1987, understood some of its muted connotations.

Nayakan (1987) is perhaps one of the most memorable characters played by Kamala hasan, a role in collaboration with Mani Ratnam’s skill for careful detail. The film is a narrative about Velu Nayakar, who grows up in a life of vigilante-justice in response to a range of social situations.

30 years ago, visiting the film sets of Dharavi was an archaeological experience, produced by thota tharini, at Venus Studios in Madras. It is a testament to Mani Ratnam’s vision of Bombay, from the heart of Alwarpet in Madras.

Kamal Haasan’s incarnation of Velu Nayak from youth to old age is complemented by three basic elements of Mani Ratnam’s architecture: the harsh reality of Dharavi, the colonial architecture of Bombay and the warm interiors of Nayakan’s home.

Mani Ratnam Calls for a collaborative synergy with some of the most iconic artists in the industry: Cinematography by PC Sriram, Art Direction by Thota Tharini, Music Score by Ustad Ilaiyaraaja, Entire Cast (Saranya, Karthika, Dilli Ganesh, Janakraj, Nasir et al), Fine editing by Lenin, Vemuri and Vijayan and the confidence of the makers in the project.

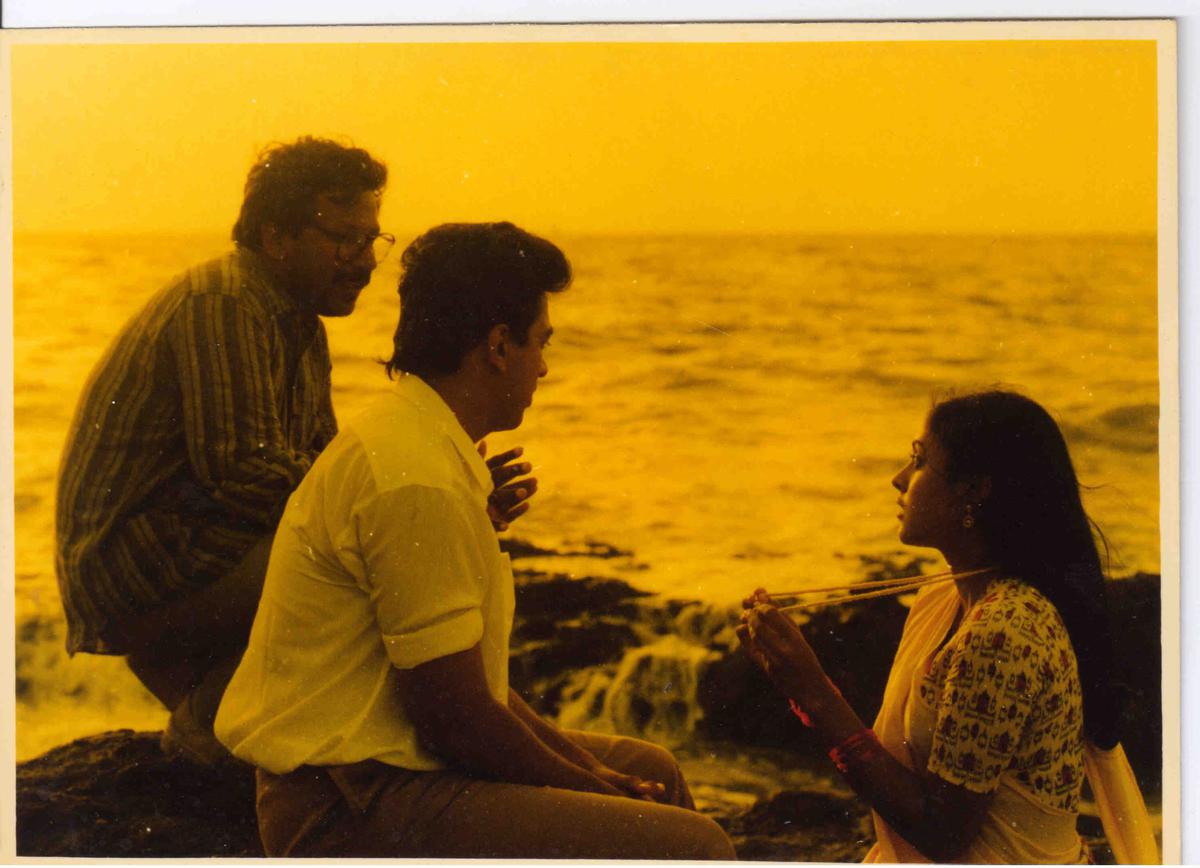

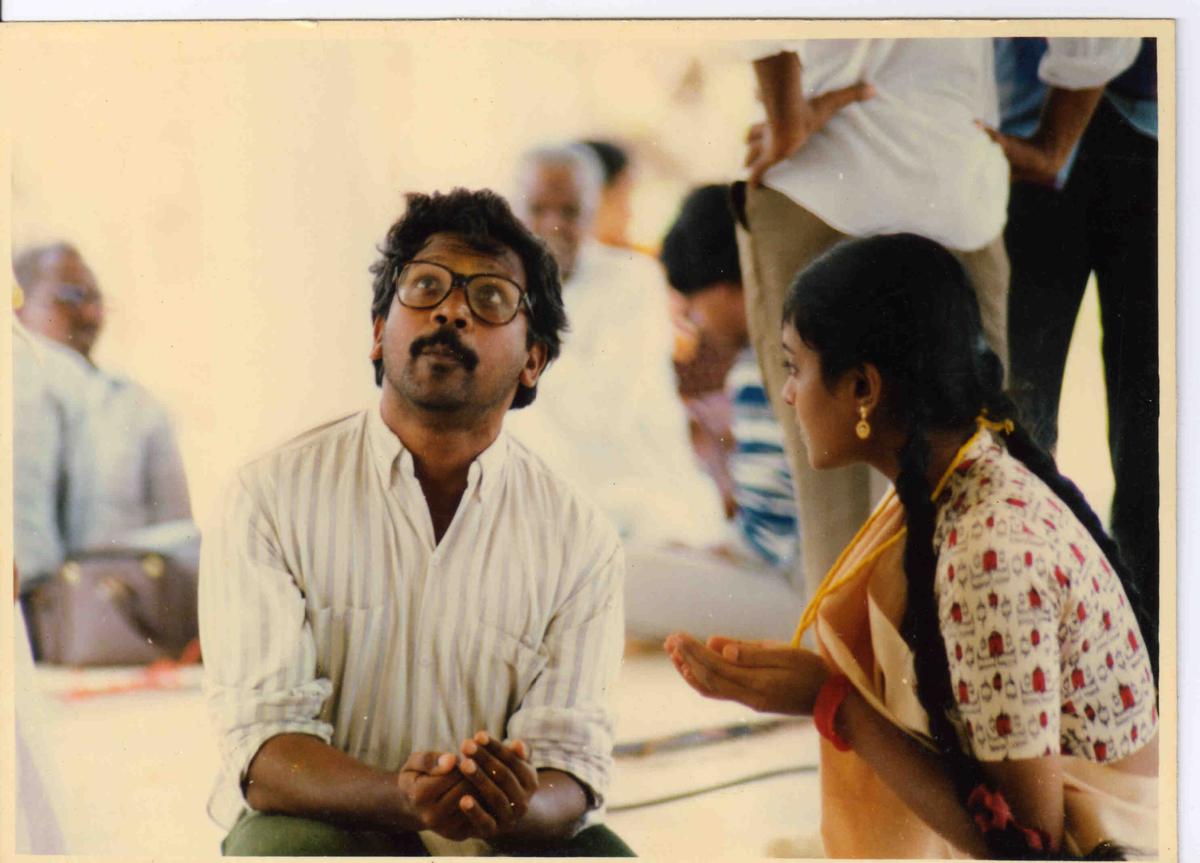

A still of ‘Nayakan’ | photo credit: Madras Talkies

rebuilding a place

What is the context of the film and how was Bombay rebuilt in Madras? Pre-Digital India (1980s) survived without mobile, internet or social media. This was the stage before its transformation from a socialist-republic to a fast-paced, consumerist society. Later Madras and Bombay were renamed as Chennai and Mumbai. Factories were closing with trade union leaders fighting for labor rights. Hardworking Tamil immigrants were moving to Dharavi, Matunga and Sion in Bombay.

The story begins on the quiet shores of Tamil Nadu: Velu, a young boy, is running into a shoot-out among the trees, following the death of his father, a trade-union leader. Velu avenges the death and flees to take shelter in the slums of Dharavi. She is adopted by foster-father living in a small, dark room. Thus begins the strange life of vigilance-justice. Like “montage cinema” of the 1920s, the film set at Venus Studio unfolds with fragmentary events, and is woven together by incredible storytelling.

Set philosophically describes the conditions of informal slums in our cities, which are treated as illegal villages, and are rarely included in urban development plans. Forced to live out of legal status, they remain vulnerable in challenging social situations.

A still of ‘Nayakan’ | photo credit: Madras Talkies

On the screen Ratnam’s Dharavi, “the world within the world”, conveys a deep sense of interiority of the narrow labyrinthine streets and a large communal open space for commerce, festivals and celebrations, delicate huts made of tin-sheets and plywood planks . PC Sriram’s tight and graceful cinematography resonates with Tharani’s set to create an intense compression of “frame within a frame”, and high-contrast shadows.

One evening, during my visit to these abandoned sets, the torrential rain-storms of Madras blurred the lines between the real and the imaginary. However, the hero’s rain on the screen had turned into a translucent blue-grey fog of uncertainty. Few directors can invoke the spirit of rain like Mani Ratnam with its aura, magnetism and mystery. In contrast to Kurosawa’s abstract rain, Ratnam’s rain embodies a raw Indian climate, expressing a variety of emotions: celebration, remorse, fear, fury and compassion.

attention to detail

Looking back after 35 years, it was formidable for Thota Tharini and his colleagues to rebuild Dharavi. Madras, Every element was crafted artistically, from small temples, plinths under trees, pavilions for musicians, Cuddapah stone floors, a mirror in the room, a wooden bridge, small shops, carts, scattered cars. of tyres, cloth ornaments, lamp shades, furniture, ponds and roads.

Looking at the abandoned bungalow on the film’s set, its spacious rooms echoed Nayakan’s delusional awe of vigilance-justice. On screen, the house is transformed, presenting each phase of Nayakan’s inner life. An allegorical score by Ustad Ilaiyaraaja complements the chronology of the ages.

A still of ‘Nayakan’ | photo credit: Madras Talkies

As a young boy, Velu finds refuge in a foster-father’s home in Dharavi. Married, he moves into a house that expands slowly, though with dripping roofs, a few coves, and starry windows. As Nayakan matures, intimidated and respected, the house further transforms into an old colonial bungalow with high ceilings and two entrances. The living room is now formal with vintage furniture and an extensive British veranda.

The cinematography, however, reveals the interiors of Nayakan’s house in fragments. We never get the complete picture of the house from outside. To quote Martin Scorsese, “Cinema, after all, is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Mani Ratnam recounts the shocking effects of Nayakan’s house leading Velu Nayakar to face a turbulent life.

Courtyard

The unshakable experiences of good and evil are absorbed by the calmness of the open sky, the courtyard of Nayakan’s house. The shading hovers in the sky, providing a drone-like, aerial view to the mute viewer. From the death of the wife and son to the confrontation with the daughter, Aangan softens the psychological intensity. This void space, the haunting question constantly – “Neanga Nallavara Ketavara?” as his daughter pleads with Nayakan to give up his life of crime.

A picture of ‘Nayakan’ | photo credit: Madras Talkies

Aangan invokes a feminine voice of resistance and a daughter’s inner resolve to face her invincible father. It is a courtyard, except for a small plant with barren leaves, where she used to play as a young child, imitating Nayakan, her child-brother. This is the same courtyard that a distressed mother receives when she rescues her child at Sion Hospital. For many years I returned to this forgotten courtyard; In an inner sanctum, which was open to the sky, an intuition of Ratnam’s architecture harbors many vulnerable memories, both pleasant and sad. Architecture tells a story and embodies hidden meanings. Popular imaginations of institutions such as police-stations, prisons and high courts are expressed by British colonial buildings; Brick-red façade, with stable porches and long arched corridors.

In the end, a relentless campaign by an assistant commissioner brings Nayakan to surrender. The final scenes depicting the Bombay High Court are ironically filmed Engineering College, Guindy in Madras. In these portals of justice, Nayakan atones his grandson and is acquitted by the courts, but is shot by a policeman’s son to avenge his father’s death.

The Venus Studio film set and Anna University (Guindy) were the delusional stage for Nayakan: an elaborate film about the fragility of human relationships and the emptiness of violence. The audience can draw their own interpretations on the spirit of poetic justice. For those who have experienced life 35 years ago in Madras, where the film was made, it is strange that Nayakan is harboring memories of a distant Bombay, which lives on in our minds.

The author is an architect and artist based near Vedanthangali