Can a biennial “competition” become the focal point of nurturing and sustaining dance makers in the country? As PECDA closed in Bengaluru last weekend, it gave some answers

Can a biennial “competition” become the focal point of nurturing and sustaining dance makers in the country? As PECDA closed in Bengaluru last weekend, it gave some answers

“This is my first video on insta… old school basic l hop I like it [hope you’ll like it]Dancer and choreographer Pradeep Gupta’s first Instagram post on February 10, 2017 reads. He dances for the camera in a corridor weaving large movements around the metal, tile and wood around him. Behind him, a man plays with the key to the locker, while a third man walks towards the camera, smiling at Gupta as he walks.

After five years and 211 Instagram posts, Gupta shared yet another update – a picture of himself with the Contemporary Dance Award in Nature Excellence (PECDA) trophy. Gupta was the 2022 winner of the biennial open-entry dance competition organized by the Prakriti Foundation last weekend.

The winner of PECDA 2022 Pradeep Gupta with the trophy. , Photo credit: Sharan Deokar Shankar/Prakriti Foundation

Gupta’s victory sealed five editions of the PECDA since it began in 2012, with a hiatus in 2020 due to the pandemic. Every two years, dance makers based in India are invited to submit a short video and proposal for a new performance made for a proscenium venue. In 2022, 57 artists applied, of which 18 were shortlisted to perform at the Bangalore International Centre. Five performances were selected for the final. Bangalore-based dancer-choreographer Parth Bharadwaj finished runner-up with his solo work untold, While Kolkata-based Promita Karfa’s Aki Buki: Simple Madness, The performance, along with Abrar Saqib, received a Special Jury Mention.

As the winner, Gupta receives a grant of ₹5 lakh to develop his 10-minute sketch into a full-length work, along with performance opportunities in a multi-city tour. He will be guided by French choreographer Rachid Ouramdan, a 2022 PECDA jury member and director of the Chaillot-Theatre National de la Danse in Paris. Ouramdane is a veteran of the National Choreographic Center of France (Centre Choreographic National), a nationwide network of choreographic hubs that aim to strengthen the French dance scene.

Ranveer Shah, founder of Prakriti Foundation. , Photo credit: Sharan Deokar Shankar/Prakriti Foundation

perspective matters

over the years, the creation of PECDA’s JuryComposed largely of experts from the Global North, prepared by Criticism For the context and relevance of your decisions. what approach And audience Is the jury represented when it decides whether to support the demonstrations made in india — actions that often respond to local crises and concerns,

Ranveer ShahThe founder of Prakriti Foundation says that the ecosystem of contemporary exhibits in India is dependent on international support. “This is one of the reasons why we presented the work that ended with some of our friend and dancer who have either been a part of PECDA or are friends of PECDAReferring to Shah a demonstration by former contestants and local choreographers, who ran with the competition section. Having invited local and international programmers, Prakriti expects the creations to be displayed Occasion To tour and make extensive appearances.

For former winners, PECDA has helped expand the scope of their work. Bengaluru-based dancer-choreographer Deepak Kurki Shivaswamy did a solo and few works within educational programs when he won the inaugural edition in 2012. The award allowed him to create an evening’s length work. Speaking about the dance environment in India at that time, he says, “In the early 2010s, there were few venues that offered the environment and skill set to create dance work. Gati was Summer Dance Residency, Attakkalari Biennial and FACETS Residency, and PECDA. These projects exposed more creators to work in the process.”

2014 and 2016 winner Surjeet Nongmikapam from Imphal shared this sentiment. “I was concentrating on solo work, but after winning the PECDA, I had to make a longer version of the piece and had the opportunity to start working with other people. Manipur is also very isolated, so the award was a contemporary one. It has been helpful to meet others at the dance.”

From the fledgling scenes that Shivaswamy describes, the contemporary dance landscape in India has evolved to include training programmes, residences, festivals and some grant opportunities. Most initiatives are funded by an uncertain mix of individual and institutional donations and money raised from classes or demonstrations. But more shows mean more participants, and contemporary dancers are increasingly likely to come from non-metropolitan areas.

Gupta, for example, hails from a working class background in Bhilai’s Maroda. She debuted in 2014 with hip-hop and breaking, and picked up her early dance vocabulary from TV. Participating in local dance reality shows in Chhattisgarh, she won a scholarship to do a short training stint at Terence Lewis Dance Academy in Mumbai. There, she studied a range of “professional” dance styles, the practices that constitute the terminology of reality TV and Bollywood, learned techniques, and also understood what interests her as a producer.

‘Under Observation’ by Pintu Das. , Photo credit: Sharan Deokar Shankar/Prakriti Foundation

watching the performance of Kamshet Project By the Terrence Lewis Contemporary Dance Company, he was influenced by the images and ideas presented by the artists. “I saw animals, a man kissing a woman and then the audience applauded. It felt natural. I felt the urge to do something worthwhile, and stopped running once I was on TV,” he says.

Gupta performed as runner-up Purnendra Meshram in 2018 Two men, A choreographic process that he credits with helping him process his thoughts and understand the way they are realized in the performance. The lockdown saw Gupta, like many other dancers, scrambling to find a strategy to survive. He was offered support by the artist Nathaniel Parchment of Goa Dance Residency. In loneliness, struggling to feel connected to the field, he began working with wooden sticks, a prop that took him back to his childhood.

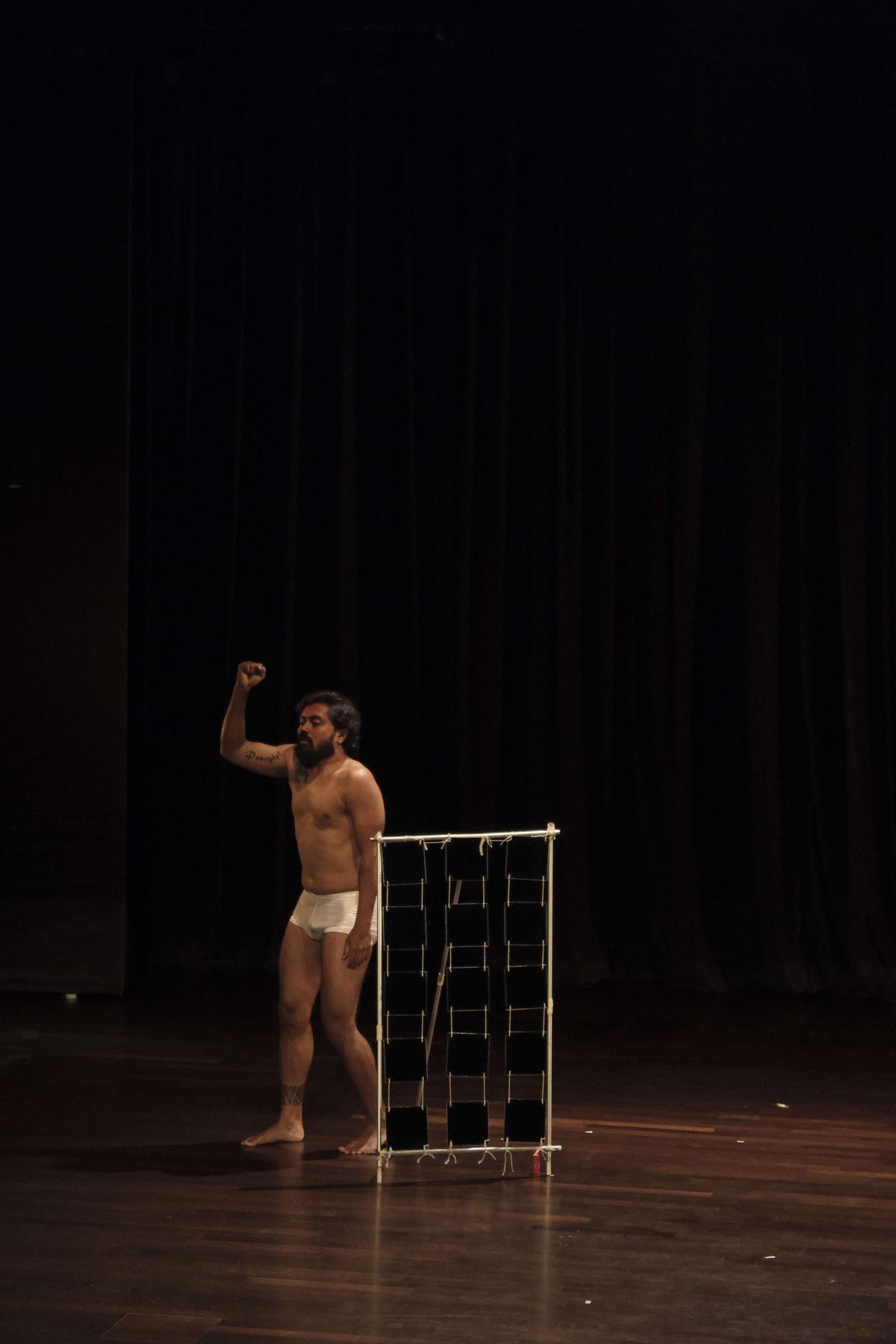

Pradeep Gupta performing his masterpiece ‘Bindadevi’. , Photo credit: Sharan Deokar Shankar/Prakriti Foundation

Bindadevi, His PECDA piece, emerged from that separation. Over 10 minutes, Gupta crosses a pool of light, tying two wooden sticks between his arms and legs. He should walk with the poles, making small, sinuous movements – a wave of the shoulders, extending out from the upper back. The sticks define his movement, but also impede him. binddevi Gupta’s parents, Jagroshan Devi and Binda Gupta, and is based on the intergenerational dynamics of a working-class household, where the aspirations of his parents, and especially his father, shape his reality. while simultaneously working to liberate and limit them.

Winning PECDA reaffirms the confidence in Gupta’s artistic choices. “I never went to any dance school. I want to find my own technology. I want to learn from people. I want to give myself that freedom. I want to embody the movement that is coming out of my life at that time.” For such artists, PECDA is a pivotal moment in a scarce resource landscape, providing an opportunity to be seen and receive support for their work. They can also meet peers from across the country, start conversations with mentors and funders, and experience what it means to be part of a “community” or “ecosystem”.

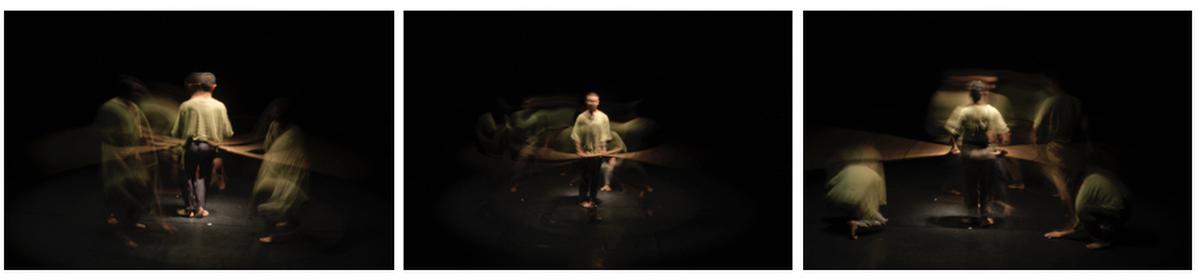

Moments from PECDA 2016 winner Surjit Nongmikapam’s ‘Meepao’. , Photo credit: Sharan Deokar Shankar/Prakriti Foundation

paris model

PECDA is based on the Danse Elargie, an annual competition held at the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris. Contestants must submit a 10-minute task with at least three performers. Danse Elargie finalists receive a contribution of €2,000 towards the cost of their participation. In this year’s competition, PECDA 2014 and 2016 winner Surjit Nongmikapam is a finalist for his work ‘Meepao’.

But how does the one-week-long biennial event foster a sense of community? PECDA’s current artistic directors, Chandrika Grover Raleigh and Farooq Choudhary, are looking forward to addressing this. “Supports where one can. Institutions and initiatives have been actively expanding their roles to include the pastoral, and the past two years are a learning in this direction. We need to see this within communities. There is a need to actively move toward a dedicated recognition of mutual care,” says Grover Raleigh.

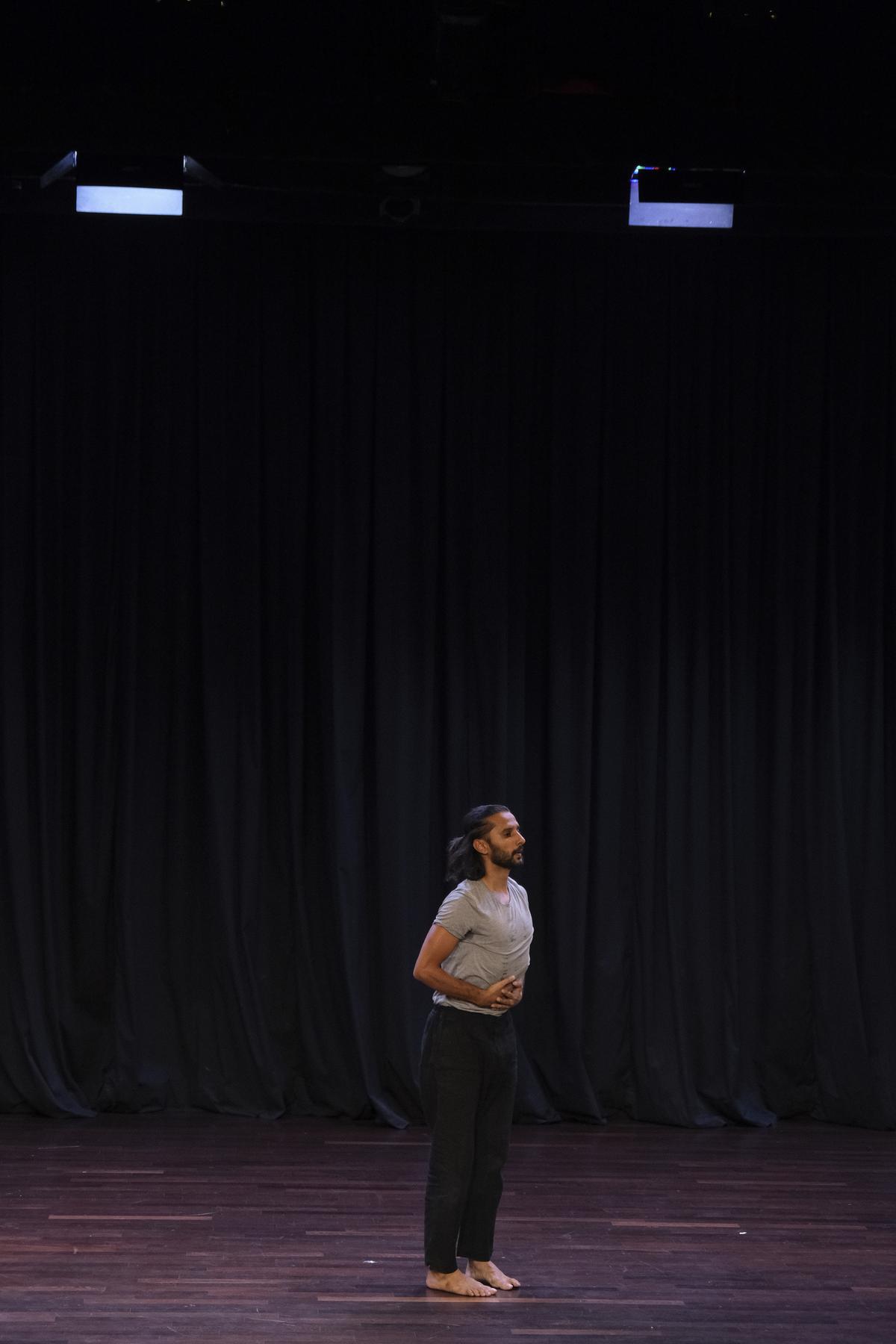

Inlines by Parth Bhardwaj. , Photo credit: Sharan Deokar Shankar/Prakriti Foundation

PECDA, which works about its model, and its challenges, has become a site for critical questions about mobility, support structures, and the hierarchies established between global north and south. Could a “competition”, a term Grover Raleigh insists he hates passionately, become a starting point for a more sustained relationship between an institution and the communities it brings together? What does equitable interdependence look like? These are questions that the dance community must answer collectively.

The author is a dance practitioner based in New Delhi.