“We are basically urban miners—the more lithium the world consumes, the more we have to recycle,” said Nitin Gupta, the founder-CEO of Noida-based Attero Recycling. “Our process is just cheaper and better for the environment.”

Today, India has a capacity of recycling over 60,000 tonnes of lithium-ion batteries annually. While the global capacity is much higher at 1.6 million tonnes per year, industry experts are confident that capacities in India will continue to rise.

Currently, recycling is the only way India can produce critical minerals such as lithium. Under the National Critical Minerals Mission, approved earlier this year, the government plans to invest Rs 1,500 crore for incentivising recycling projects.

“When the PM keeps using words like circular economy, recycling, and critical minerals in his speeches, you know the government’s focus is on these matters,” said Rajat Verma, the founder of Lohum, during a sponsored media visit by ThePrint to its facility in Greater Noida. “Battery recycling is the future because critical minerals are the future.”

What is recycling?

Lithium-ion battery recycling is a relatively new industry, with various reports pegging its worth from $6-$10 billion annually, according to Fortune Business Insights and MarketsandMarkets. It involves dismantling used and end-of-life battery packs from smartphones, laptops, electric vehicles, and other devices to reuse individual parts and raw materials.

“At the end of its life, the battery loses charge, but its essential components remain the same—so, why can’t we reuse the components?” explained Vinayak Singhal, Assistant Vice-President at Lohum.

The most significant component of a lithium-ion battery is the cell, which contains nearly 60-70% of the value. First, recycling companies collect and shred the cells to produce a ‘black mass’. As the name suggests, it is a black powdery substance containing all the minerals that went into making a battery—lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese.

“The real challenge is to get the minerals out of the ‘black mass’. Everything until then is just a mechanical process,” says Bhawan Purohit, Executive Director at Rubamin, one of India’s top lithium recycling firms and a multi-national company with an office in Vadodara, according to BDO India, which is involved in business services and outsourcing.

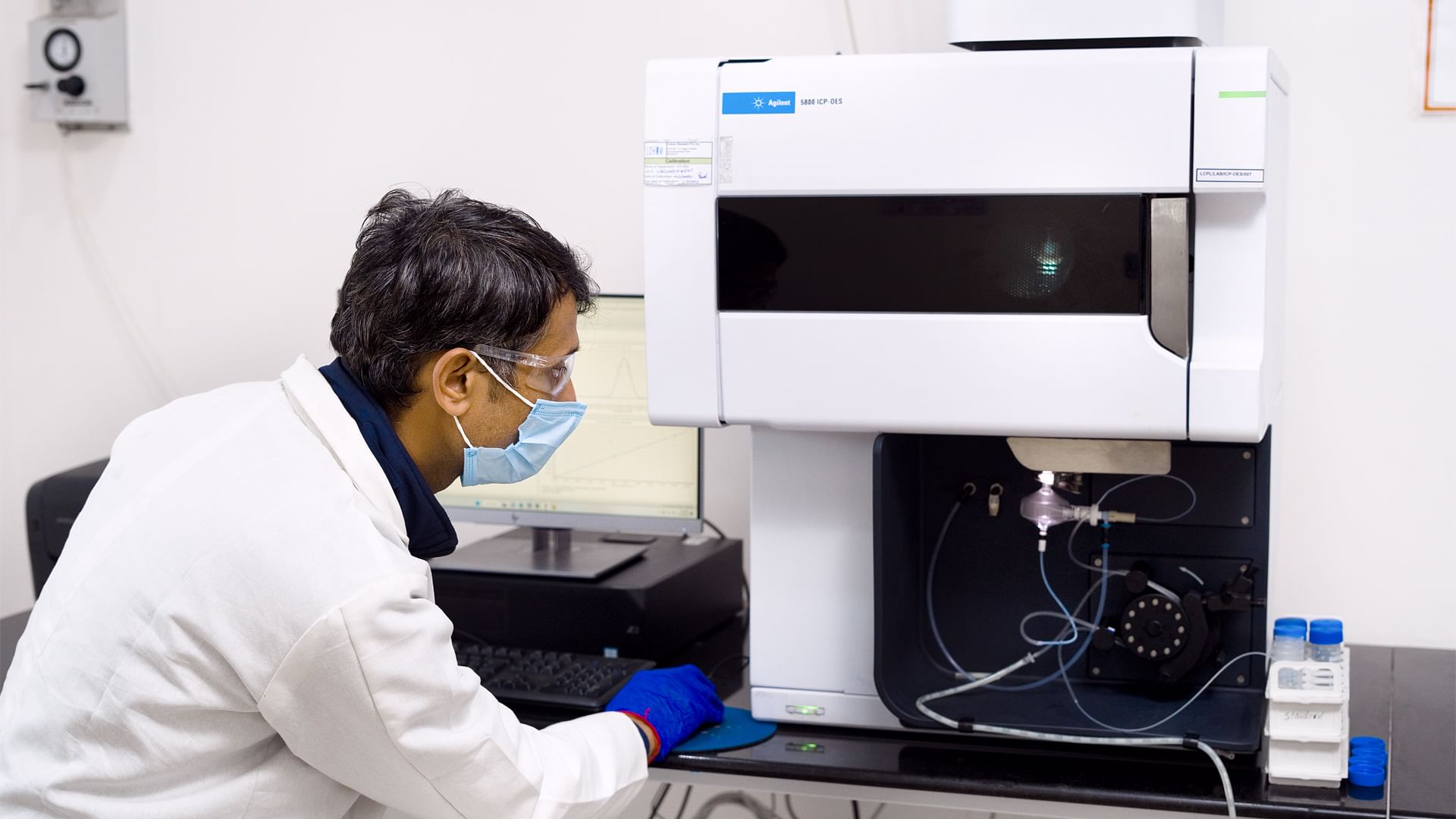

Companies have developed their respective technologies to recover minerals from the ‘black mass’. There are two broad processes of recovery—hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy. The former, which Lohum and Attero use, is a chemical leaching process, where the ‘black mass’ is dissolved in solutions, and minerals are extracted in a liquid form.

At Lohum’s Reclaim facility in Greater Noida, massive piles of the ‘black mass’ sit on the factory floor, waiting to be mixed with solvents and processed into lithium carbonate, the “common form” usually used to recover the rare mineral. The recovered lithium is packaged and sold to industries to make batteries, glass, pharmaceuticals, and defence products. Some of the lithium recycled in Indian companies is exported to battery manufacturers abroad. Currently, India does not have an active manufacturing capacity for lithium-ion batteries.

According to a BDO India report, India has the capacity to recycle 60,000 tonnes of battery material yearly, yet numbers vary. A Deloitte China report pegs India’s battery capacity much higher at 89,000 tonnes, but most in the industry agree that it is somewhere between 50-60,000 tonnes with more being added every quarter. By their own testimonies, Lohum contributes 20,000 tonnes out of this, Attero 17,500 tonnes and Rubamin 10,000.

Of the total 60,000 tonnes, only 50% gets converted into ‘black mass’, amounting to 30,000 tonnes of material, from which minerals are extracted. In one tonne of ‘black mass’, there is nearly 10% lithium on average. So, from the 60,000 tonnes of battery material, approximately 3,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate is produced. That amount is enough to power 1,00,000 electric vehicles—not insignificant, given how nascent India’s recycling industry is.

By 2030, according to BDO India estimates, the country’s production capacity will increase from 60,000 to 5,34,000 tonnes. Ken India, on the other hand, has estimated that the Indian battery recycling market will be worth $10 billion by the same timeframe.

“Companies that prioritise efficient recovery methods and build robust domestic supply chains will not only lead in market share but will also play a pivotal role in reducing India’s dependence on imported battery materials,” said Harsh Saxena, the associate vice president of Ken Research.

Also Read: India’s shift to EV is making China richer. Over $7 bn paid in 5 years

Critical minerals in India

Rajat Verma, an alum of IIT Kanpur and Harvard Business School, hit upon the idea of sourcing lithium from discarded batteries back in 2015. Verma and Lohum’s co-founder Justin Lemmon, a former US military man, noticed a common trend in their countries. The US and Indian governments were only waking up to the importance of critical minerals in key industries such as clean energy and mobility.

“Back then, we were not in a position to go and invest in a lithium mine, so we wondered what’s the next best thing?” said Verma. “Recycling was the answer.”

Ten years on, in January this year, the Indian government approved its National Critical Minerals Mission with a plan to invest Rs 34,300 crore over seven years.

On the other hand, US President Donald Trump said he wanted access to rare earth minerals in Ukraine earlier in February this year.

“There’s been a huge recognition by the Ministry of Mines and MNRE [Ministry of New and Renewable Energy] of the fact that critical minerals are indispensable to India’s growth,” said Saloni Sachdeva, an energy specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). “This recognition comes with the acknowledgement that most of the supply chain lies in China and that we need to develop indigenous capacities immediately.”

An October 2024 report by the IEEFA says that India currently has 100% import reliance on minerals such as lithium, cobalt and nickel. Moreover, roughly 60% of the world’s lithium is mined and refined in China, adding a geopolitical risk angle to this import reliance. India is already in talks with other countries in Latin America and Africa to develop bilateral relations to access minerals such as lithium and cobalt from them, and the Geological Survey of India is exploring reserves within the country.

In this context, Sachdeva described the “immense role” of battery recyclers such as Lohum and Attero in critical minerals production in India. Despite being recyclers with basic-level capacities, these companies are the sole contributors to any critical minerals that India is currently producing.

“Even after locating and auctioning mines, it takes at least 15 years for it to be operational and produce minerals in a viable manner,” said Sachdeva. “Until then, if we are to make a dent in our import dependence for critical minerals, it is through recycling and refining.”

Challenges to recycling

On paper, it seems perfect that recycling gives new life to critical minerals and reduces the presence of hazardous e-waste in landfills. E-waste had reached a whopping 1.71 million tonnes in 2024 in India. Yet, the world over only about 5-10% of all lithium-ion batteries are recycled, with the rest ending up as garbage. Complicated processing, expensive recycling infrastructure, and absence of end-of-life management systems act as barriers to battery recycling.

An analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that despite the steady rise in the battery recycling industry, it will only have miniscule effects on the total lithium demand in the world until 2025. By 2050 though, recycling will be able to lower the demand for lithium by mining by 25-50%, found the analysis.

Right now, China massively dominates the battery recycling sector, as other green energy sectors, in number and technology. Many of its lithium battery producers have built recycling facilities. Contemporary Amperex Technology Company Limited (CATL), China’s largest battery company, and the world’s largest battery recycler alone can recycle 1,20,000 tonnes of battery material annually. That is double India’s entire recycling capacity at the moment.

Rubamin Executive Director Purohit and Lohum founder Verma flagged another challenge for the Indian recycling market—battery material.

“In India, most lithium batteries are from smartphones and laptops. Our EV deployment happened so recently that those batteries have not run their course yet,” said Purohit.

Attero, Lohum, and Rubamin also import battery scraps, a product recently exempted from basic customs duty by the Union government, from other countries.

Verma explained the varying Extended Producer Responsibility rules across countries, some mandating original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) take back the used batteries from the consumers.

“In many countries, these OEMs just give the battery material to us for free. But in others, we have to pay them for it—so, the supply chain for battery recycling is still under configuration,” he said.

Purohit said that many battery recyclers in India are operating at lower than their full capacity, due to the unavailability of used material.

“In a few years though, we’ll see a slew of batteries from two and three-wheelers pouring in, as the first generation of Indian EVs will finally reach end-of-life.”

Indian recyclers—a ray of hope?

The graph for recycling is only going up.

“You have to understand that lithium recycling is not even 10 years old. While the world adapts to electric vehicles and more lithium use, the battery recycling ecosystem is evolving too,” said Nitin Gupta, the CEO and co-founder of Attero.

With contracts for facilities in the UAE and US, Verma is confident of a scale-up in his operations. He is waiting for a huge investment in research and development.

“Why does China have such a huge capacity? What has China done better?” asked Verma. “They have invested in research and development,” he answered.

Verma has organised the Lohum employees in the way companies do in China’s Shenzhen city special economic zone, home to the biggest Chinese brands, Huawei, BYD, and One Plus.

Sitting in the crowded research wing of his company in Greater Noida, Verma said, “Chinese recyclers will have 10 people on the factory floor but 50 in the research room, developing newer technologies.”

Just a few miles from the research wing is Lohum’s sparsely populated recycling factory.

According to Verma, his company spends roughly five percent of their annual revenue on research and development and has a patented recycling technology.

“I can safely say our technology is just as good, if not better than that of the Chinese recyclers, who are in the market right now,” he added.

ThePrint was a part of a media tour of LOHUM’s facilities in Greater Noida.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Tissue engineering, satellites—science & tech startups to watch out for in 2025