Even as it has established its presence in the global space industry as a serious competitor in recent years—with big-ticket missions like Chandrayaan-3 and now the upcoming Gaganyaan—it is still considerably behind its counterparts, such as the United States, China, and the European Union, when it comes to launching satellites.

The difference is nowhere close.

While the US averages over 50 satellite launches per year, India only has a little over 50 active satellites in space. This means the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is averaging only about four to six launches every year.

This is worrying because, lately, everything from a country’s disaster preparedness to infrastructure development and military surveillance has become dependent on how well it monitors its regions from space. Knowledge, after all, is power in the new age.

And ISRO agrees.

The newly sworn-in chairperson, V. Narayanan, has acknowledged that India needs to enhance its presence in space.

“We are aiming for a scenario where the number of Indian satellites in space will go up to more than 100 in the next three to four years,” he said.

Also Read: 2024 Physics Nobel for AI scientists. How they pioneered machine learning modelled on human brain

Low launch numbers

The Sriharikota spaceport, also known as the Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SDSC), and situated on India’s eastern coast, has been abuzz with unusual activity lately. There was a time when the only movement that this quiet island witnessed was that of trucks carrying parts of launch vehicles right before a launch.

And that, too, only once or twice a year.

Now, every few months, the empty roads leading to the launch pads of the SDSC start brimming with a cheerful crowd of families and media vans, which cover each aspect of a launch.

Things have changed for the better, but don’t be fooled by the numbers, experts say.

Government data shows that in 2024, ISRO carried out a total of 15 missions, but of these, only nine were launch missions. And of the nine launch missions, only five were tasked with placing Indian satellites in orbit.

Similarly, in 2023, the Indian space agency conducted seven satellite launches. Of these, only three were Indian satellite launches. In the global satellite race, these numbers are significantly low.

Last year, the US accomplished a record 154 orbital launches. In 2023, their orbital launch numbers stood at a solid 110.

China is also not far behind. In 2024, China conducted 68 orbital launches.

Srimathy Kesan, founder and CEO of Space Kidz, an Indian aerospace startup pioneering in design, fabrication and launch of small satellites, spacecraft and ground systems, told ThePrint that India needs to up its marketing game and ease procedures if it aspires to compete with spacefaring nations like the US and China.

“Elon Musk’s SpaceX is practically ruling the space industry currently. Even China has realised the importance of having a marked presence in space and has upped its game,” Kesan said.

She said that most of India’s own space companies are also trusting SpaceX to launch their satellites for ease and reliability.

“To book a launch with SpaceX, all one needs to do is fill a form, which is extremely straightforward, and they will give you a launch slot,” Kesan said.

Because of frequent launches, Musk’s SpaceX is also able to provide the lowest launch costs to its passengers, she said.

In India, on the other hand, the process of booking a launch is a little more complicated.

The booking process is overseen by IN-SPACe (Indian National Space Promotion and Authorization Centre), the commercial arm of ISRO, which is the primary agency facilitating private sector involvement in India’s space programme.

If an Indian company wants to book a slot for a satellite launch, they need to submit a detailed proposal, undergo evaluation, and finalise a contract with IN-SPACe for the launch.

Foreign companies must undergo additional regulatory approvals and security clearances before they can book a launch with ISRO.

Industry insiders ThePrint spoke to said that once a company completes all the formalities with IN-SPACe, it would take anywhere between 12 and 24 months for the final launch to happen. With the US’s SpaceX, however, the wait time is only about six to 12 months.

A senior ISRO official, who wished not to be named, told ThePrint that India is also trying to follow the US way in the coming years. By promoting more private players in the domain, ISRO aims to transition into the role of a governmental research and exploration organisation—similar to NASA—while complementing private companies that can take over the task of providing launch services.

“We have just started opening up our space sector for private players. Once these companies expand their capabilities, we will also be able to increase our commercial and strategic launches,” the official said.

Also Read: Search for an Indian Carl Sagan is on. Science influencers are being trained in labs and likes

Colonising space

Space wars are no longer fiction.

David Ignatius, a columnist with The Washington Post and a novelist, says that the first space war is already happening between Ukraine and Russia.

Military movements are being monitored through satellite surveillance, strikes are being thwarted due to unprecedented battlefield awareness, and strategies are being devised to disrupt navigation systems.

India gained this knowledge the hard way back in 1999. During the Kargil War, India had requested the US to provide access to the Global Position System (GPS) to identify enemy locations, but was denied.

This exchange prompted the Indian space agency to begin strategically designing its own answer to the GPS—Navigation with Indian Constellation, or, NavIC.

A standalone navigation satellite system, it is currently used on a regional scale, but will be developed in the coming years as a ‘Made-in-India’ global satellite navigation system. This is expected to be comparable to the US’s GPS, Europe’s Galileo, or China’s BeiDou.

While India’s NavIC currently has seven satellites in orbit, its second instalment of satellites—launched in January this year—faced a setback after the thrusters failed to ignite, hindering the planned orbit adjustment.

Data shows that as of 2024, the US has around 4,500-5,000 active satellites in space. This accounts for over 60 percent of all operational satellites globally. China has nearly 450 operational satellites, while Russia has around 200.

According to data provided by the Department of Space, as of 2024, India has 54 operational satellites.

Earth observation satellites, including the Cartosat, RISAT, OCEANSAT and the GSAT series, perform functions such as weather, disaster and military surveillance. But for places where India’s satellites don’t reach, agencies rely on foreign satellite data.

Many space enthusiasts have argued that India’s space ambitions might be “misguided”.

In March, ISRO completed a 1000-hour test on the 300 milliNewton Stationary Plasma Thruster, which was developed for induction into the electric propulsion system of satellites.

This electric propulsion system is set to replace the chemical propulsion system in future ISRO satellites, paving the way for communication satellites that use only electric propulsion systems for orbit raising and station-keeping.

But experts say that such advancements are getting overshadowed by larger missions like Gaganyaan—India’s first human spaceflight mission which is due to be launched around 2026.

“I have been waiting for this for the past 15 years. Increases the effective payload by 40-50% for all launches. This and much better launchers (aka NGLV). Instead, we jumped on to Gaganyaan. Speak about misplaced priorities,” science communicator and space enthusiast Indranil Roy said in a post on X.

But many also argue that this is a harsh and unfair judgment of India’s rapidly developing space programme.

An aerospace engineer, who recently quit ISRO to join a private space company, said a primary reason behind India’s low launch count is its limited launch capabilities. India still relies on small and medium-sized launch vehicles, which have limited payload capacity.

“What India lacks in resources, it makes up for in skill. We do have some limitations, but that has not stopped us from making some significant advancements in the field,” the 30-year-old engineer said.

So, progress might be slow but steady.

Retired Lieutenant General A.K. Bhatt, the current director general of the Indian Space Association (ISpA), told ThePrint that India has recognised the necessity of deploying its own surveillance satellites rather than relying on foreign inputs for satellite coverage of its own region.

“It would be unfair to compare satellite numbers between countries. A better marker of comparison would be how these satellites are fulfilling a country’s requirements,” Bhatt said.

He said that the government’s Space Based Surveillance (SBS) project will be a big push for Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) satellites in the coming years.

Last year, the government sanctioned Rs 27,000 crores to launch 52 ISR satellites in the next five years under the SBS-3 project. These new satellites will complement the existing satellite systems, enhancing India’s capabilities for better surveillance over its land and sea borders.

Changing focus

In 2014, when ISRO successfully put its Mangalyaan robotic probe mission (orbiter) around Mars, The New York Times published a cartoon.

It portrayed a stereotypical depiction of India featuring a farmer—dressed in a kurta and dhoti—with a cow knocking on the doors of the “elite space club”. Inside were some tea-sipping westerners, reading about India’s Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) in the papers.

The cartoon might have been distasteful, and the NYT was forced to apologise and recall it, but ISRO chose to respond to this through its work.

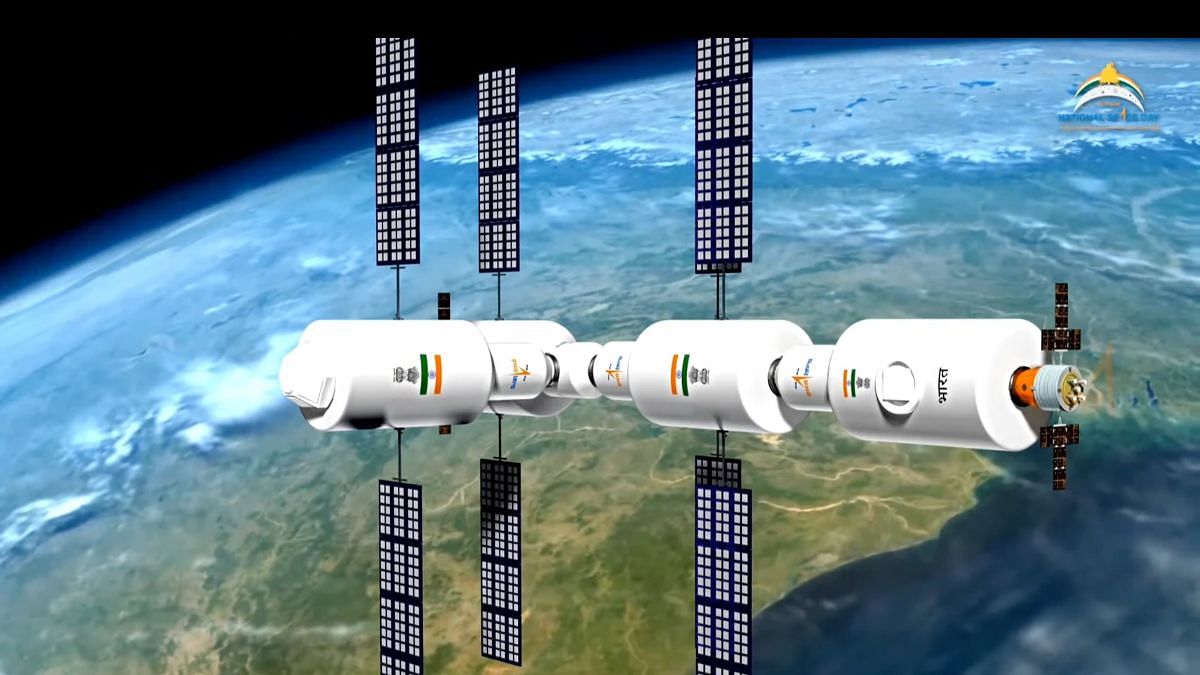

With the success of Chandrayaan-3 in 2023, India became the first country in the world to land near the lunar south pole. In the same year, it launched a first-of-its-kind satellite, Aditya-L1, to study the Sun. It is now preparing to build its own space station—Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BSS)—similar to the International Space Station (ISS).

NASA has also partnered with India for launching the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR), designed to provide detailed measurements of the Earth’s surface and monitor various environmental changes using advanced radar technology.

“The next decade is very exciting for India’s space programme. Of course, there are areas we need to improve, but that is the case with every agency. Even NASA did not reach where it is today overnight,” former ISRO chief S. Somanath told ThePrint.

But one thing is clear. While ISRO has miles to go, it has undoubtedly joined the “elite space club”.

(Edited by Radifah Kabir)

Also Read: Posture panic hits researchers. IITs, AIIMS, big hospitals use smart microscopes now