Form of words:

IIn the summer of 1935, the Indian Air Force, less than its third anniversary, was facing an existential crisis. Two of the five pilots before this had fatal accidents and a third were dismissed. The remaining two, Flying Officer Subroto Mukherjee and Aizad Baksh Awan, were by then finding their feet advising the seven additional pilots who had joined the IAF. In addition to their dwindling numbers, the new organization also faced problems from some lobbies in the British establishment, who did not see the need for a colony for their air force.

Part of his plan to derail the fledgling Indian Air Force included offering juicy civilian portfolios to Mookerjee and Awan – assistant commissioners in Burdwan and Peshawar respectively. But these men were made with a different subtlety. As Awan later recalled in his memoirs, he told Mukherjee, “… inform Flight Lieutenant Boucher that when we were in school we set out on the task of building up the Indian Air Force. Many of our dears Companions have been killed in the conflict. We will leave this struggle only when our dead bodies are pulled out from the wreckage of the crashed plane. (D) Indian Air Force will be formed, and we will continue this struggle [sic]As history was to witness, his perseverance paid off – certainly with the substantial help of his commanding officer, Cecil Arthur Boucher.

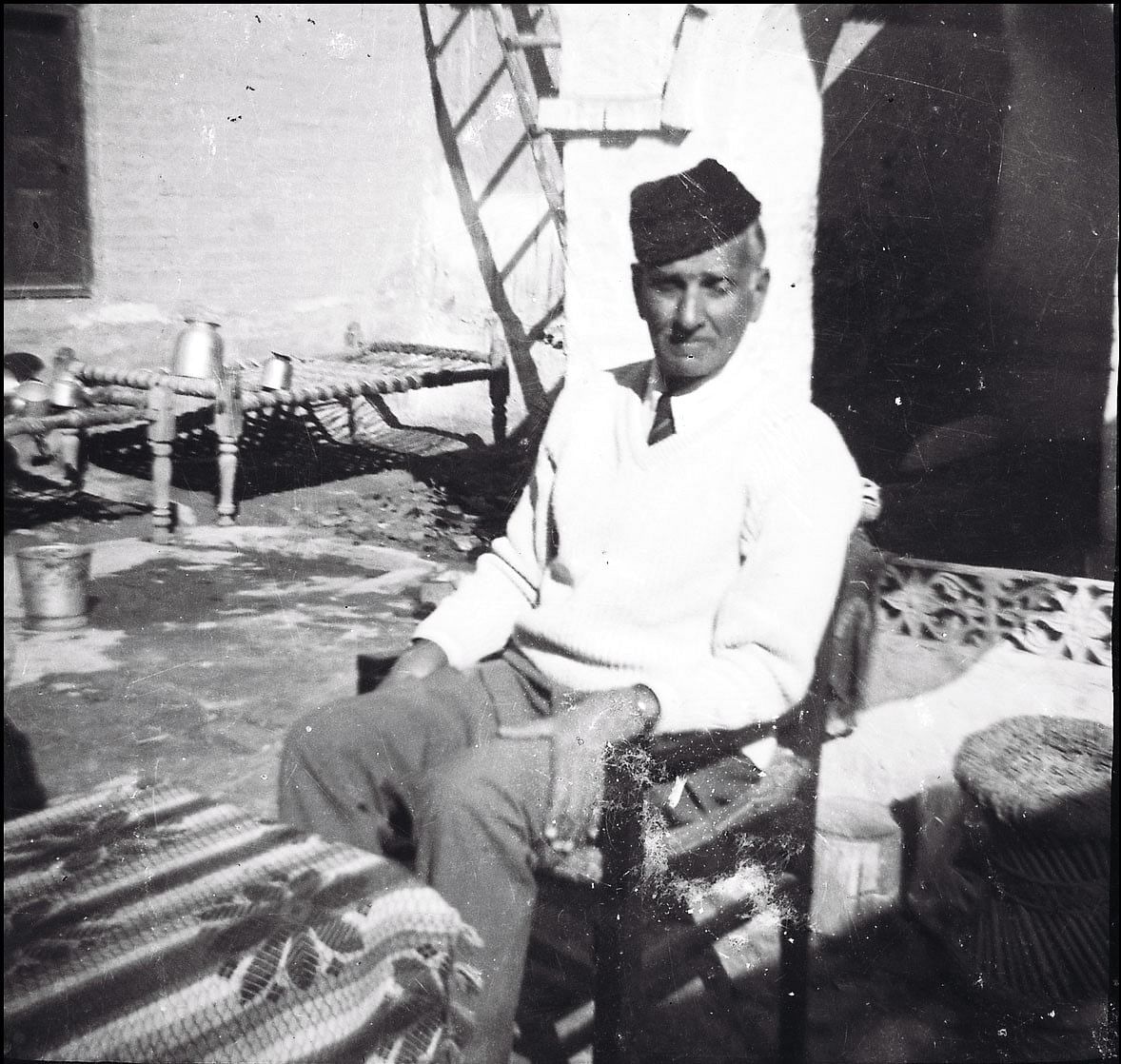

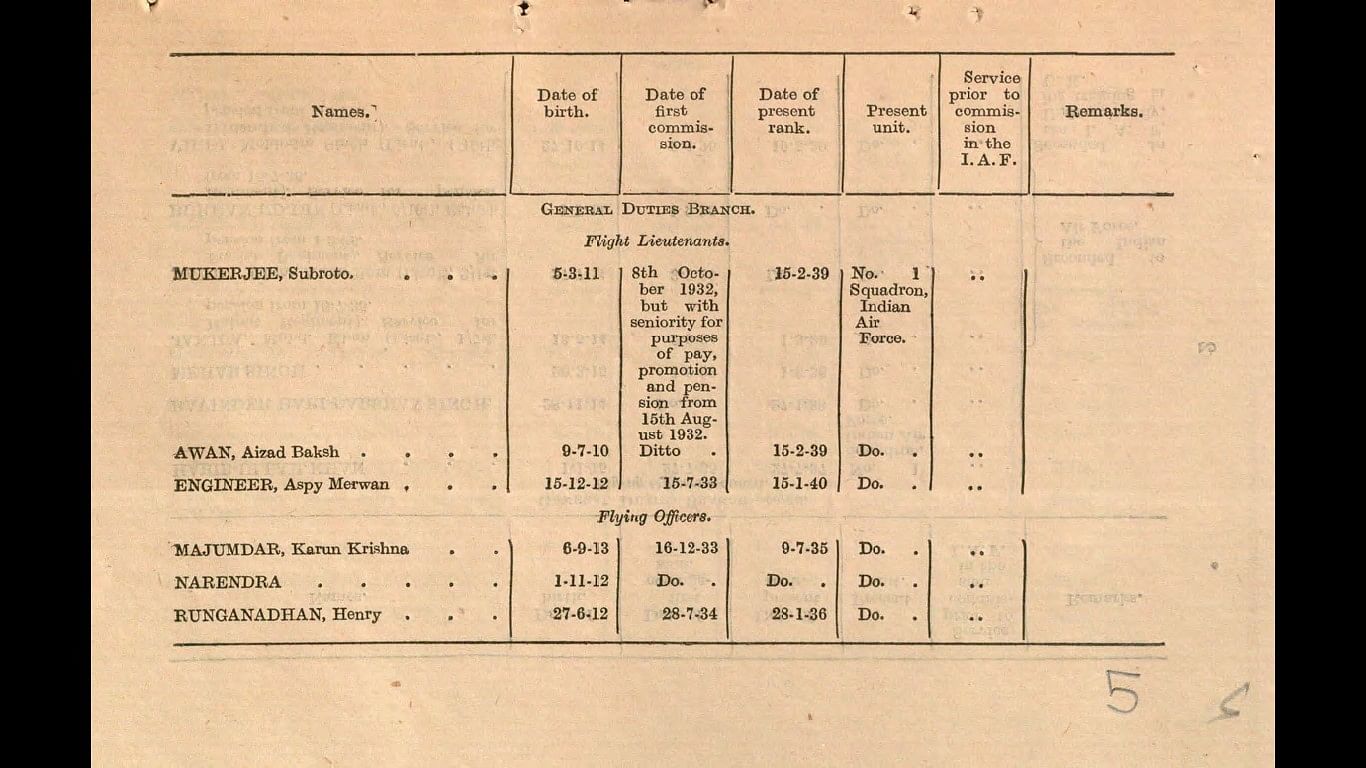

Awan was from a prominent family in the city of Dera Ismail Khan in the North-West Frontier Province. Born on 9 July 1910 in Mianwali, Awan developed an early fascination for flying when he saw an Airco DH.6 flying over his school. However, his dream of flying an aircraft had to wait until the birth of the Indian Air Force was approved by the Skene Committee in 1927. Soon, the six-foot-striped Awan found himself on his way to England for training at the Royal Air Force (RAF) Cranwell. . At just 20 years old, Awan must have wondered what the future would hold for him and his five teammates – Mukherjee, Harish Chandra Sarkar, Amarjit Singh, Bhupendra Singh and Jagat Narayan Tandon.

His training at Cranwell included flying on aircraft such as the Avro Lynx, the Armstrong Whitworth Atlas and the AW Siskin. Between flying and classroom training, Awan, nicknamed Zaidi, found ample time to excel in sports – captaining the tennis and hockey teams of RAF Cranwell and later the Indian Air Force until 1944. Awan and four other Indians were commissioned as pilot officers on 15 August 1932. .

After landing at Drigh Road in Karachi in March 1933, he was received by Flight Lieutenant “Boy” Boucher, who would become his commanding officer, guide, mentor and friend for years to come. At this time, the IAF consisted only of No. 1 Squadron IAF’s “A” flight, consisting of four Vapi aircraft. Assigned an Army support role, his early time in flight was spent conducting extensive exercises in close formations, reconnaissance, puff shoots, front camera gun attacks, message hanging on a string, bombing targets and aerial mosaic photography, etc.

In May 1936, when the squadron moved to Peshawar, Awan was buzzing with excitement at the prospect of flying over the charming though wild country. On 20 March 1937, Awan and the IAF flew their first operational mission, in which Awan took K1263 Wapiti to drop leaflets on Arsal Kot, warning the locals of an imminent air attack. However, Avan did not fire a single bullet in anger. The summer of 1937 was soon their chance to arrive.

Avan later remembered a specific flight around Razmak, when he was flying in support of ground operations, “My air gunner Ghulam Ali saw the ground signals and patted me on the back. I selected the bomb fuses and made the nose and tail guns come alive. As I began to dive on the target, the bomb release lever was placed in the neutral and ready position. The bomb was dropped. In the same dive I fired a short burst of machine gun fire at the front. After exiting the dive I placed the machine between the target and our soldiers and asked Ghulam Ali to fire from the rear Lewis machine gun. This was repeated many times.“

As the operation closed in November 1937, Awan was assigned the task of aerial photography of the victorious Bannu Brigade. Upon finding no troops in the area, Awan found, to his horror, that the “victorious” brigade was attacked by about 3,000 Aborigines. Mehsuds apparently didn’t get the ‘Victory Parade’ memo! As the melee disintegrates into a melee involving “hand-to-hand combat”[ing], with daggers and bayonets”, Awan and his number 2, Karun Krishna ‘Jumbo’ Majumdar, launched several bomb and machine gun attacks in defense of the hapless brigade. Having exhausted all his gunpowder, Awan went back to the Mirali cantonment and dropped a handwritten message asking for reinforcements to be sent.

This characteristic of empathy and the habit of going out on a limb for others would define Awan throughout his life. Be it his involvement in ensuring that his men lived and lived in good housing or that devotion to duty, when he flew in a surgeon to operate on a British woman, lived according to the social code of the Awan Pashtunwali. Ironically, he was also campaigning aggressively against tribals with similar beliefs, and one can only imagine what psychic demons he might have fought or potential hostility that might have come his way from fellow tribesmen.

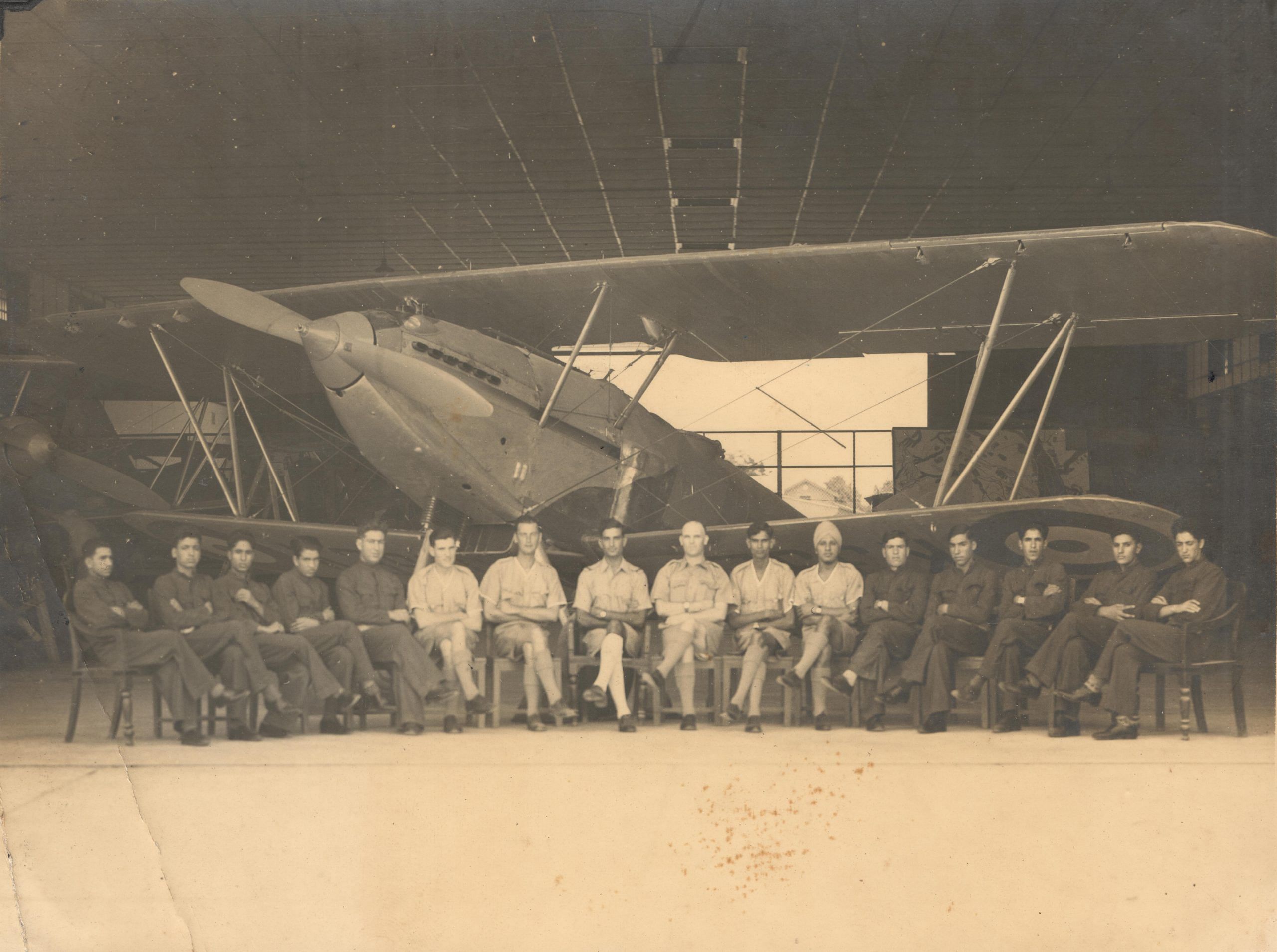

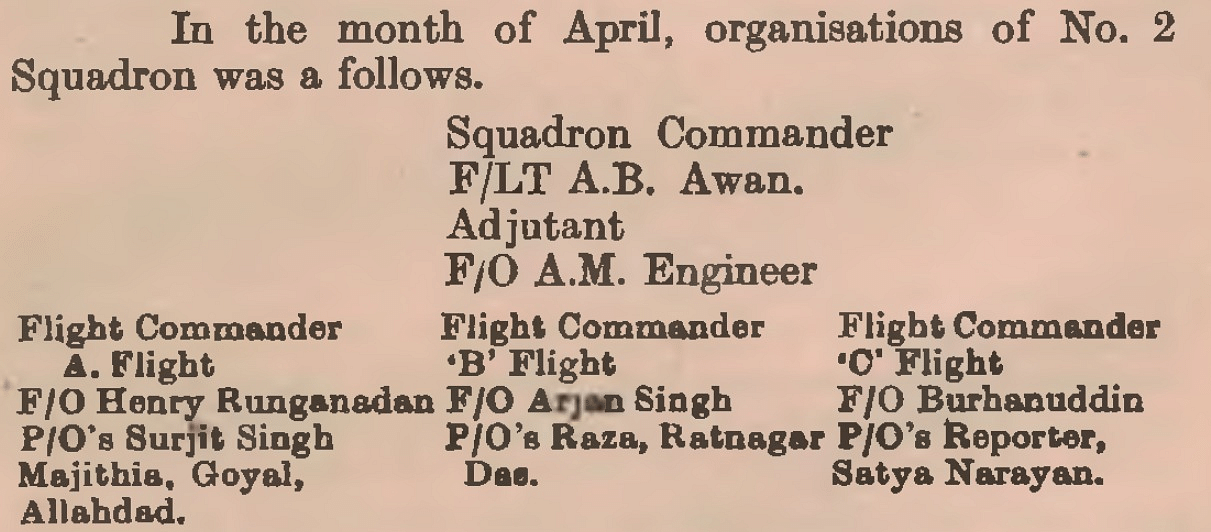

Awan’s experience was put to good use when he was selected to provide flight training to Afghan Air Force cadets. After being assessed as “what it takes”, Awan was also placed on the selection board for appointment of Army officers to the growing Indian Air Force. By now, Awan had been out of action for too long and was itching to return to the squadron, which had grown to three flights, now commanded by Mukherjee, Espy Engineer and Jumbo Majumdar. In December 1938, Awan replaced Mukherjee as “A” flight commander; The latter assumed the role of Unit Adjutant.

During Awan’s tenure as Flight Commander, the squadron was converted from Wapiti to Hawker Hart and Audax aircraft. He also led a redesigned “Q” flight equipped with Hart aircraft for naval support and coastal duties in Karachi – a completely unfamiliar task that would have seen him oversee extensive training. After this, Awan married Taj in April 1939. When the second IAF Squadron was being sanctioned in February 1941, the responsibility of raising and commanding it fell on his experienced shoulders.

However, he was to command No. 2 Squadron for only three months, handing it over to the Espy Engineer. He departed from Peshawar for Delhi to oversee the operations and training of the IAF, replacing Mukherjee. Over the next few years, Avan and Mukherjee charted career paths. They were both sent to the Staff College in Quetta, and replaced each other in Air Staff postings at the Group and Air Headquarters. In October 1942, when the Indian Air Force decided to allot service numbers to its officers, Mukherjee was awarded 1551 and Avan 1552; But being course-mates, they were both promoted to parent squadron leaders on the same date. However, by 1943, their paths began to part ways.

In August, Mukherjee became the first Indian to command an RAF station in Kohat. Awan was sent to America on a “military goodwill” mission. On his return, he found that Jumbo, his junior, had been promoted and left for Europe to fly with the RAF. Espy, who was also his junior, was also about to be promoted and RAF Kohat was taken over from Mukherjee in late 1944.

Awan felt humiliated and repeatedly represented British officers but found himself flying with 152 Operational Training Unit at Peshawar, then attached as Supernumerary Crew to 82 Squadron, RAF at Ramu near Cox’s Bazar Gaya. He was repeatedly interviewed with RAF Air Commodores to “Cut No Ice” and in May 1944, he was asked to take charge of No. 7 Squadron. A shocked Awan informed the squadron but politely refused to take command, instead going on leave. Awan never flew for the Indian Air Force again.

His family further says about this period- “The Chief of Air Staff clearly told Awan that there were limited vacancies. Awan said he would resign from his commission if this happens. The chief advised him not to take hasty decisions. Awan left the chief’s office but wrote his resignation letter in the PSO’s room and took the train to Peshawar. after about three weeks, He Received a telegram from AHQ stating that they needed to report to the chief. During this final meeting, Awan told the chief that he did not wish to serve anymore. The Chief said that in that case he would be given premature retirement with the original rank of Wing Commander.

Finally, one can sympathize with Avan, a pioneer whose career came to an end in such an anti-climatic manner. He helped establish the fledgling army, led it into battle, fought for his men and was considered a master of military cooperation. His deprivation of command of a station remains an unfortunate mystery. Had he stayed with the rapidly expanding Indian Air Force, he might have got what he deserved. Retired at the time of the division, Awan did not join the RPAF, where he could once again reflect the career of his course-mate, rising up the ranks to command his Air Force, becoming the Chief of the Indian Air Force.

Awan’s love for the IAF was so great that he self-published his autobiography in 1955, dedicating it to the IAF. He died peacefully in 1989 in Karachi. His autobiography contains a series of recommendations that he felt both the Indian Air Force and the PAF would receive while wishing the best for both the air forces.It will keep our soul happy when we are no more. We created the first nucleus of the Air Force in our homeland“

The service profile of Wing Commander Azad Bakhsh Awan can be seen here – https://bharat-rakshak.com/IAF/Database/1552.

Anchit Gupta @ AnchitGupta9 is an aviation history writer and is currently co-authoring a book on the role of IAF in the Kargil War. Thoughts are personal.

(edited by Prashant)

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay a price to maintain this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.