If you want to know whether AI will diminish what people are paid relative to what they produce in a typical workday, you can ask AI.

Yes, ChatGPT recently informed me in typically bloodless prose, “this outcome is highly likely.” But it’s also, so I was told, “not inevitable.”

The productivity-pay gap has been a nagging concern for decades. It often takes a backseat to worries about so-so productivity gains, but even those gains appear to have outpaced wages. Increased automation played a role in this. Now, the advent of ubiquitous AI means it won’t just be assembly-line workers marginalized by high-tech shortcuts, but also the university-educated masses toiling at what’s typically called knowledge work.

That segment of the global workforce emerged from the last big wave of technology disruption in a relatively privileged position. This time, it may incur a segmentation of its own. People don’t generally list “traditional managerial technostructure” on their LinkedIn profile, but it includes a lot of white-collar workers angling to not only remain employed, but earning a wage that rises in line with the value they generate.

A recent field study of software developers newly equipped with AI assistants drew a bright line under the matter at hand; the least-experienced and lesser-paid were able to deliver the biggest relative productivity gains, suggesting that their more experienced colleagues suddenly lack justification for earning higher wages.

At a time of dwindling financial security for middle classes, this could be an issue.

Seizing the material opportunities presented by change instead of tiptoeing around it may not be as straightforward as it sounds, at least for the average cubicle dweller. But research on AI-induced job insecurity suggests it can be softened by instilling self-efficacy; a belief that people can control their professional fate may lead to more active augmentation, and less ceding ground.

Equipping as many as possible to manage their own “teams” of AI tools would be ideal. That would mean ensuring that as many as possible have access.

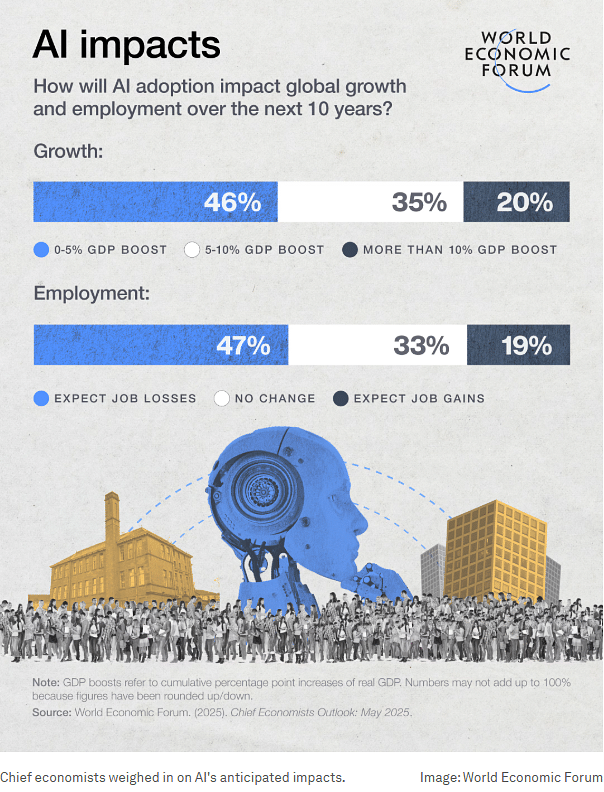

Nearly half of the chief economists surveyed for the Forum’s latest Chief Economists Outlook think “worker augmentation” will be one of AI’s biggest benefits for economic growth, but “increasing inequality” ranked among their biggest assessed risks. Three out of four said government spending on “upskilling and redeployment” should be a priority.

Produce more with AI, earn more… right?

According to standard economic theory, productivity and pay should basically rise in tandem (Karl Marx had some things to say about that). Beginning in the 1970s, wages began decoupling from productivity in the US and Europe. Japan followed with an even more dramatic disconnect in the ensuing decade.

The cited causes include a concentration of pay raises among people in more senior positions, a general shift of income away from workers to shareholders, and a greater tolerance for unemployment if it means keeping a lid on inflation. Meanwhile automation, while it’s created a lot of winners, also inevitably results in losers.

The size of the productivity-pay gap we’re left with can vary depending on how it’s measured.

If you exclude the people in supervisory roles who tend to receive what pay increases are available, and compare the bulk of workers left over in the private sector to overall productivity, the gap is yawning. A more closely matched comparison results in something less glaring. Proponents of both approaches agree on one thing: productivity needs to accelerate, and quickly.

There’s some debate about when AI will help with this in a meaningful way. It seems clear that some workers are already able to use it to do far more with less.

The question is whether fewer people will be able to share in any future benefits of this increased productivity. Wanting to supply as many employees as possible with the best tools and training isn’t necessarily the same thing as doing it.

There are already signs of what the new cast of losers could look like. Displaced knowledge workers have been failing to find new positions at notable rates.

If market realities dictate the availability of fewer well-compensated jobs in these fields, that could echo earlier shifts for manufacturing in advanced economies – places that have since scrambled to recover what was lost, for reasons that can be as political as they are practical.

One of AI’s principal pioneers has said that people with jobs that involve decision-making might want to consider alternatives that utilize other things that distinguish us as humans, like opposable thumbs. Plumbing, for example. Others say it doesn’t have to be this way. That there will always be areas of human expertise that command a premium, in ways that may not only maintain the middle class, but expand its ranks.

ChatGPT offered up some of its own suggestions to me about how to deal with the situation it’s helping to create. Preventing wage stagnation will rely on reinvesting any economic gains that AI creates into skills development and “fair wage policies,” it said. Places “with strong worker protections and social safety nets” will likely fare best.

It’s not about the technology, according to the technology, it’s about how we choose to apply it.

John Letzing is the Digital Editor, Economics at World Economic Forum.

This article first appeared in the World Economic Forum. Read the original piece here.