Chennai-based Ashvita Gallery’s latest exhibit traces the origins and development of commercial art from Madras – from calendars to advertisements and, of course, cinema posters

Chennai-based Ashvita Gallery’s latest exhibit traces the origins and development of commercial art from Madras – from calendars to advertisements and, of course, cinema posters

These colors, landscapes, faces and motifs are all very familiar; We grew up seeing them on calendars, magazines and commercials. Now, apart from the occasional resurgence that capitalizes on their ‘retro’ value, commercial art is headed for obscurity. At Ashvita’s quaint gallery space, a narrative is being created on how commercial art, which dominated many homes over the past hundred years, saw a movement in Madras parallel to the rest of India.

Look around and you find, for example, a calendar that dates back to 1966: a scene depicting the Hindu god Shiva surrounded by holy devotees, attached to a masthead reading palm pillars and Fife Traders . A 1970 poster containing perhaps the most widely shared and replica painting of another Hindu deity, Balamurugan, reads: Sri Mangalambiga Stores – Stainless steel dealers and general merchants.

These widely circulated works of art are not often attributed, yet are important to the visual language of the country. “The show exists because we wanted to ask people the question: ‘What is fine art? Who categorizes it as fine art? Why does Hussain get a museum exhibition and not say, Kondraju and Aykan,'” Most of these artifacts were discarded, says Ashwin E Rajagopalan, curator of the exhibit. “They became objects of no value because they were free. Today we are able to give him a reference.”

a calendar that dates back to 1966

The focus of the performance, which brought out seven artists, does not deviate from Madras. The curators say that initially it was not a 100-year history.

It all started with the Tanjore painting of Lord Rama which coincidentally came into his collection. “At the bottom, in Old Tamil, it was said that anyone who wanted to buy prints of such artworks had to go to shop number on Broadway, dated 1888. Many such paintings were referred to as Tanjore Paintings. are classified. On paper, still in museums today. But we learned that college students would come across the lithography press on Broadway, which has been the focus of calendars, greeting cards, and posters for the past 100 years, black-and-white. to print on lithographs which were later hand-coloured. So it became cheaper and could be easily replicated. This happened around the same time that the works of artists like Raja Ravi Varma entered the printing presses.” And so, it’s hard to miss the effects. When an artist’s scenes at this scale are commercialized, popularity follows. And when these scenes stay in homes for a long time, the idea itself becomes; of gods and goddesses, landscapes and scenes.

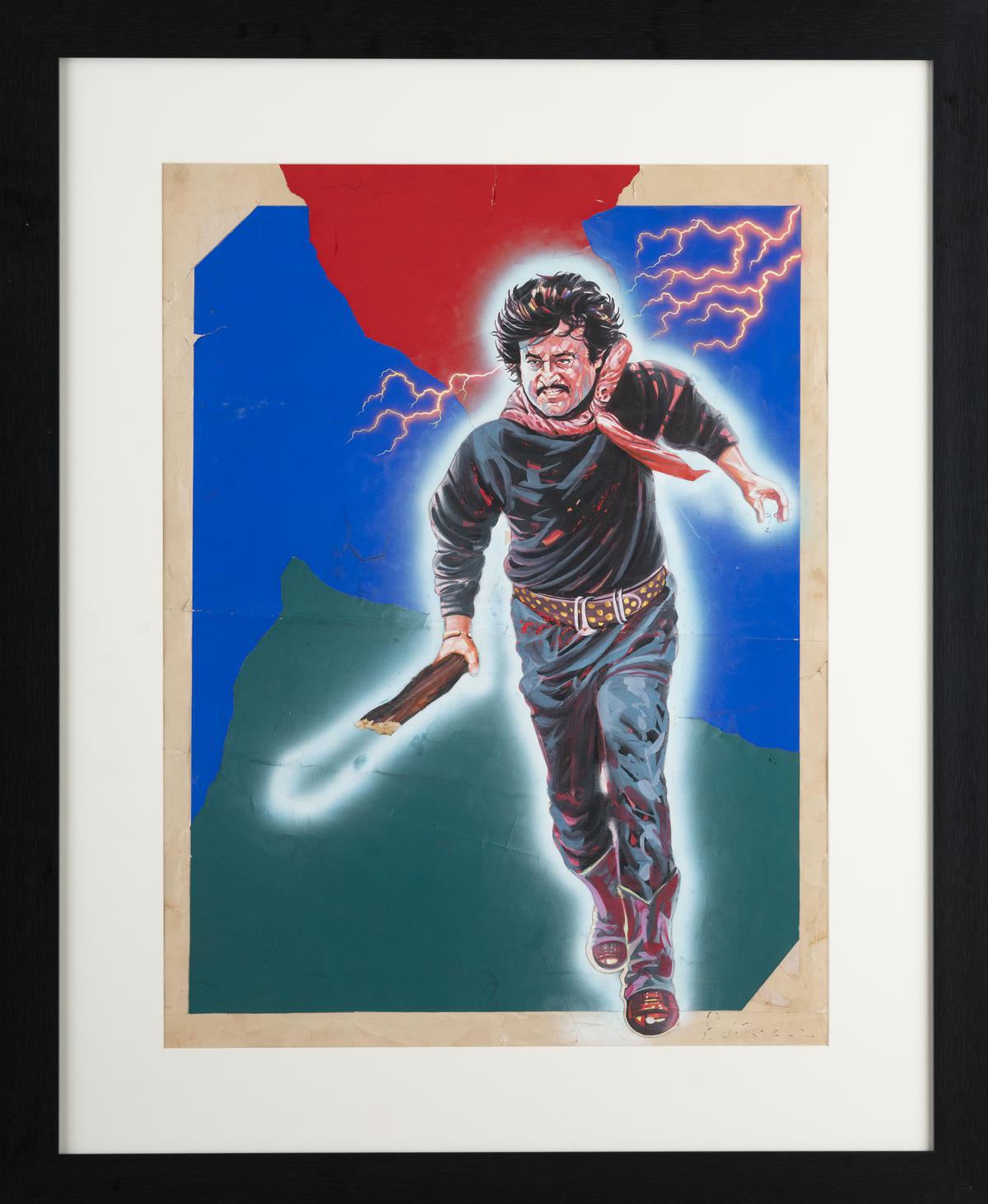

From there, the narrative depicts how the movement spread to various aspects: there are also magazine covers and calendars on display that showcase “the cutting edge Photoshop work of the time”. In that sense, they would paint, cut the font (for the text) and paste it, and send the negative of the entire panel to the press. At that time only a small number of magazines had offset technology. Anand Vikatan One of the first publications to be offset was in the 1930s. His magazines having artworks on cover were highly anticipated by the Tamil speaking population. Similarly, a set of draft designs for Rajinikanth’s film pandiyan (2000) shows hand-crafted, highly skilled work combining cut-and-paste elements.

Draft poster of Rajinikanth-starrer ‘Pandian’ (2000)

In the late 1800s photography students all over Tamil Nadu established studios. “Studio work was commercial work: in addition to photos and portraits, they would also work on greeting cards and calendars. And when you enlarge a photo, it starts to blur, and people in the studio to sharpen it. Colors give the finishing touches. Photo studios were thus the hub of commercial artists,” says Ashwin. A portion of the performance pays homage to this part of history.

A walkout in such 90 frames offers fascinating visuals for a range of art that has rarely been studied or documented. “Commercial art is not commercial in that sense. It is still built on art that is ‘fine’ like any other form,” concluded Ashwin.

The exhibition can be seen till 17th July at Ashvita, Dr. Radhakrishnan Salai.