‘The World: A Family History’ This is the most challenging and yet most satisfying book I have ever written, says Simon Sebag Montefiore. , Photo Credit: Marcus Leoni

In his new book, The World: A Family HistoryIn , British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore traces convergence and divergence in world history through individuals and families. Historian Manu S. In an interview with Pillai, he explains why this is his most challenging and yet most satisfying project. Edited excerpts:

The World: A Family History, Simon Sebag Montefiore, Hachette India, ₹1,899.

You have become an expert in tracing history through human agency. Is it a conscious choice?

With history, the human eye is very useful. And that’s what I’ve done, exploring the world through individuals and families. But I do not claim that this is everything. The world is made up of great movements of technology, trade, migration, pestilence and war. and ideologies and religions. but what have i done in this World To connect these processes, to make them accessible is to use individuals and families. So yes, history is about great convergence and divergence, but also about human agency.

Were you scared of doing ‘world history’? This is your biggest canvas.

Yes, this is an ambitious book. The idea itself is simple: it is an exposition of world history with the intimacy and juiciness of biography. This is the most difficult and yet most satisfying book I have ever written. I also faced the fact that I am not an expert on many of the topics I cover. So I turned to the experts: I consulted professors around the world, and I was fortunate enough to have several eminent people help me. You have to approach these things with humility. At first I wasn’t sure it would work. But in the end, I think it’s done.

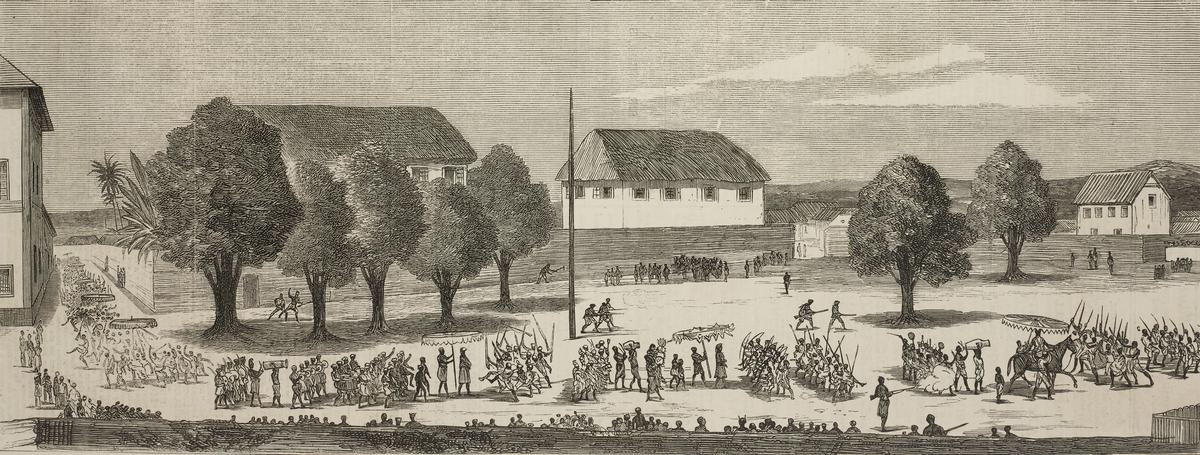

Procession of Dahomey chiefs with their slaves and bands. , Photo Credit: Getty Images

You have also tried to avoid that trap of Eurocentrism.

Yes, I was clear about diversity. I wanted to reach out to dynasties like the Mughals or the Gandhi-Nehru family in India, just as I reach out to the Ming or Tang of China, the Dahomey kings in Africa, the Hapsburgs and Windsors in Europe, and the Kennedys in America. I wanted to cover vast countries like India as well as other countries like Cambodia, Haiti, Morocco. Africa was a challenge, as there used to be an attitude that African history did not begin until the Europeans arrived. Same in America. But I took it as a challenge that I have to cover the history of these places Earlier Europeans arrived.

Coming to the family unit, despite the diversity of geography and time, when you combine power and family, you find similar patterns. And all is not pleasant.

That’s why I don’t romanticize the family. Yes it remains a basic unit of human life. And the Shakti family continues in our world. In India, Prime Minister Modi made a virtue of not being part of a political dynasty. Power families around the world tended to act in a certain way. But there are differences too. For example, in Europe, primogeniture was a strong principle, but with the Turks and Mughals, brothers fought for the throne. It was a risky system as family feuds could destroy the country. And then there are cases where the family is superlative. Queen Victoria made political alliances through royal marriages, but these relationships did not prevent World War I – as people followed the interests of their kingdom more than that of their family.

Vintage color lithograph of Queen Victoria in her robes of state. , Photo Credit: Getty Images

You also see that in political families and courts, violence – spectacular violence – was a constant.

Yes, violence is often a farce. In China, you were subjected to incredible public torture. When I first started reading, I thought they could never be used, but they were. Much of it was designed to display the despotic power of rulers and to warn against standing up to it. The killings were particularly messy. It’s a lot harder to actually execute someone when you’re in a panic. It’s one of the things about human life: the sheer chaos of many simultaneous, often spontaneous, things happening everywhere around the world.

Sexuality abounds in the book. Sons are misleading ambitious mothers by sending lovers; same-sex relationships; And so on.

This book is a celebration of humanity, as well as an indictment. So there are a lot of dark spots: genocide and war. But it also includes poetry, songs, music, architecture, and of course, given that it’s about families, sex. It is part of the richness of human existence. I’m not a conscientious writer. I enjoy writing about it, I enjoy the diversity and I don’t judge people for it. I think the whole picture of someone includes his intellectual life, his sex life, his family life and his political life. I try and cover it.

A painting that shows an early 17th-century ceremony in which musicians, elephants, guests on horseback and servants carry a tray of gifts to the home of the bride of Prince Dara Shikoh, heir to the Mughal throne. , Photo Credit: Getty Images

Sexuality is also linked to legitimacy. And one gets the feeling that the royal lines were rather mixed. You quote the Prophet Muhammad, who says, “All genealogies are lies.”

Yes, there is tension, and genealogy is an invention. The idea of dynasties and ceremonial families is a social invention, possibly designed to protect wealth and power. Similarly, the idea of going from the male side of the family is a social tradition, as families are older than that in terms of DNA and physical lineage. And historically, noble families were mixed. The Ottomans brought brides from various backgrounds. So you have sultans who were as much Serbian or Albanian as they were Turkish. In India, we see the Mughals mixed with many groups. Finally, all family history is a history of inbreeding.

The reviewers are historians and writers.