Form of words:

FOr over five decades, international environmental meetings have been affected by the north-south divide.

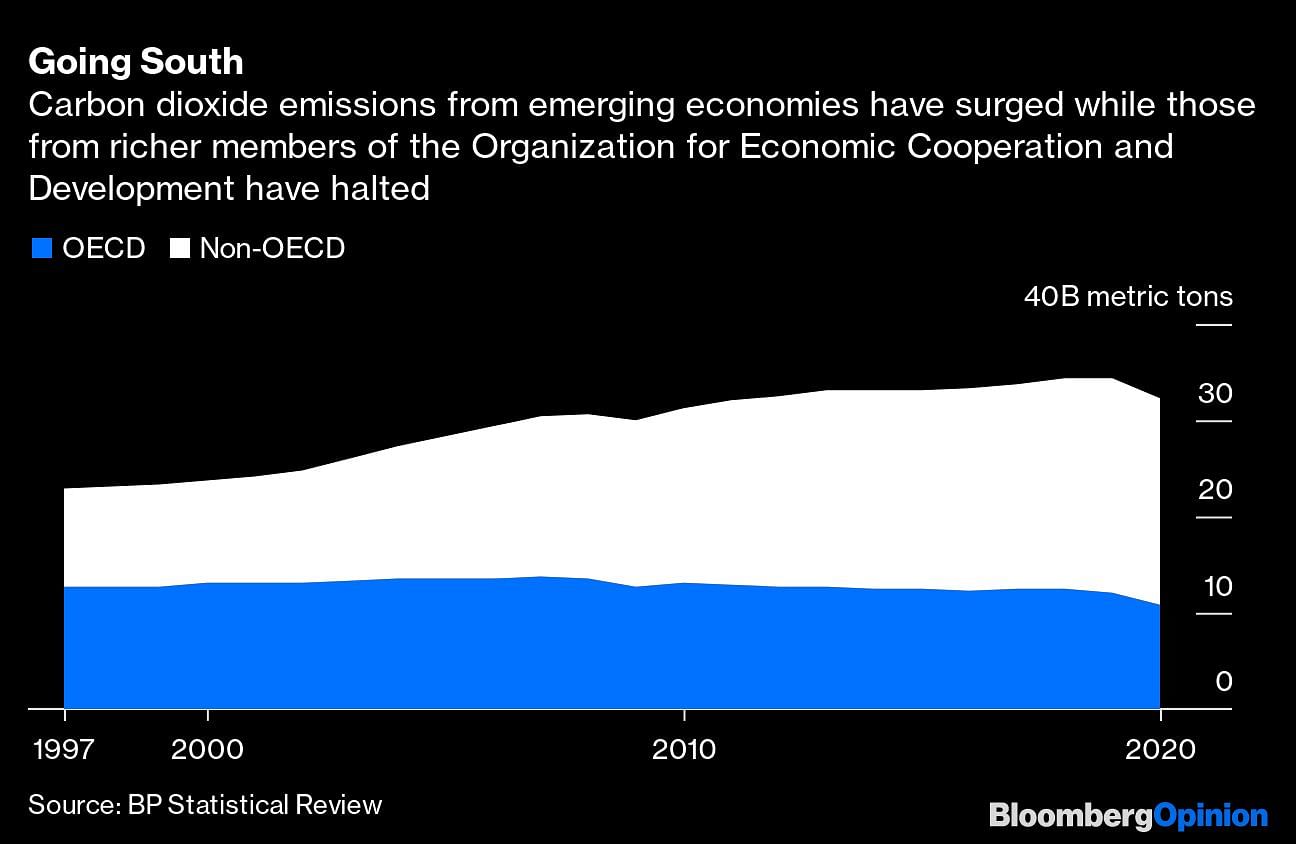

While the rich nations of the global north have led the way in calls to rein in emissions, their less prosperous counterparts have largely remained on edge. The Kyoto Protocol in short was a treaty between a wealthy group of seven countries, the former Soviet Union, Australia and New Zealand. For the first time since the 2015 Paris Agreement also brought developing countries into the greenhouse-targeted club, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development fell 2.7% in the four years to 2019, while low-income countries grew by 7.2%.

Former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s words at the 1972 Environment Conference have been instrumental in cementing that position. “Aren’t poverty and need the biggest polluters?” He argued.

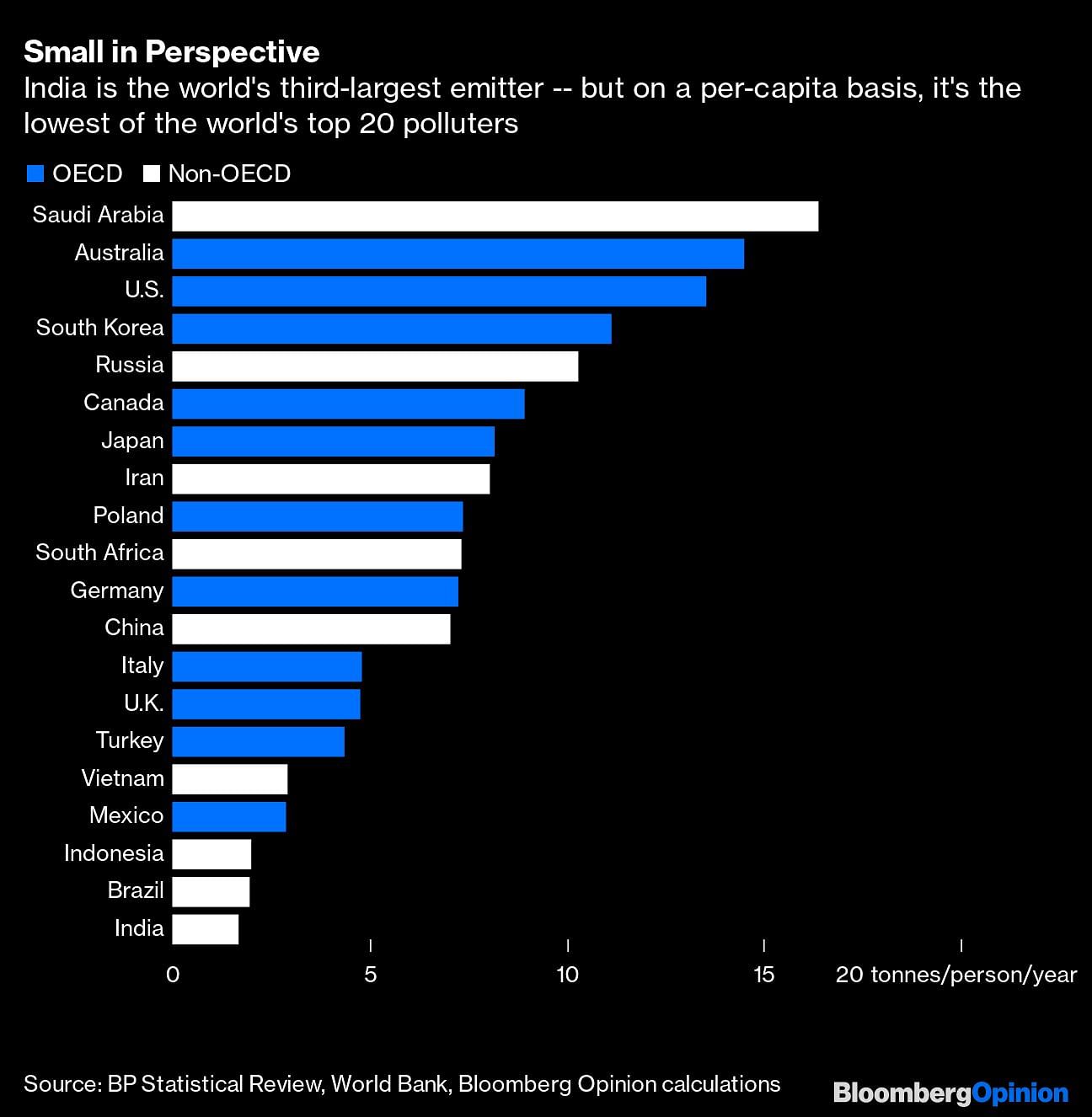

By that logic, the propaganda of wealthy countries reflects hypocrisy. Having built their own wealth on the cheap energy provided by coal and oil, they seek to deprive other countries of similar benefits. With less than a sixth of the world’s population, they have racked up more than half of historical carbon emissions. Just as they monopolized the world’s resources during their days as imperial overlords, they too have monopolized the planet’s limited capacity to absorb carbon.

Those debates are as alive today as they were then. Major developing countries in September branded the EU’s plans to impose “discriminatory” prices on the carbon content of imports. Analysts at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, a New Delhi-based think-tank, wrote in September that a equitable outcome would not see India’s emissions hit zero until 2075. Whether and when New Delhi announces a net zero target is one of the biggest unknowns of the upcoming global climate summit.

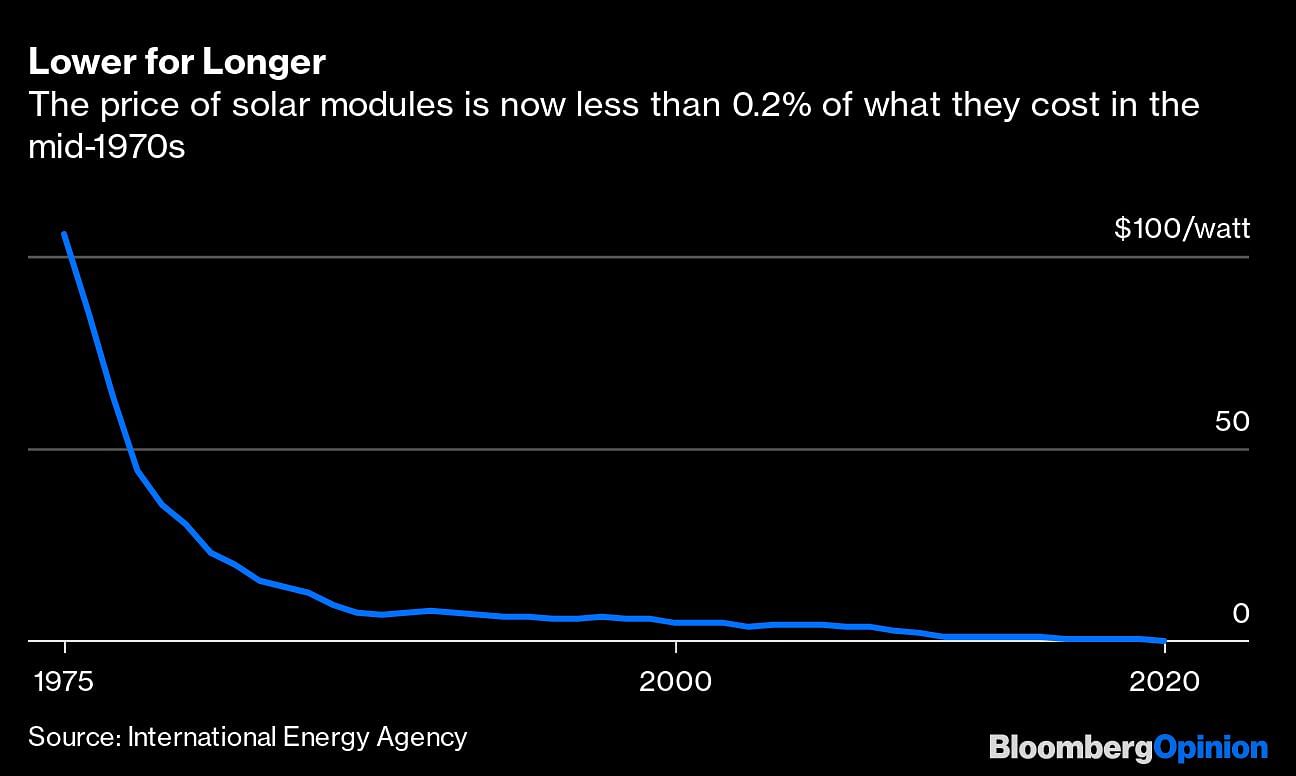

However, it is time to recognize that the logic underpinning this approach is breaking down. When Gandhi spoke, fossil fuels were clearly the cheapest way to power economic growth – but the price of rival technologies has since fallen, while the cost of continuing down the emissions-intensive path has increased by the year. Is.

In 1975 the cost of solar modules was over $100 per watt; The same amount of electricity can now be bought for about 20 cents. Even when wind and solar are not available, spending extra money to smooth out peaks and troughs of demand now results in lower overall system costs than dirty alternatives in green grids.

According to a March study by US National, India could provide 45% of its energy from wind and solar in 2030, compared to less than 10% currently in the grid, and still have the same power as its current fossil-dominated system. is the cost of. Renewable Energy Laboratory. According to a separate analysis in Nature Communications last year, in 2040 renewables would save $50 billion to generate 80% of electricity where they were absent.

In this new world, delaying the switch to zero-carbon power is not giving emerging economies a chance to catch up with wealthier countries – it is slowing their growth with higher-cost electricity when cheaper alternatives are available.

This is not to mention expenses that are not paid in dollars and cents. In India, several studies have shown that coal plants are responsible for over 100,000 premature deaths a year due to the health effects of particulate emissions. An August report by economists from the Indian Statistical Institute put the environmental impacts from mining and smog as well as its costs at 0.9% of the country’s gross national income.

On top of that, there are low quantifiable expenditures due to health problems that do not result in deaths, as well as the loss of competition from cities so polluted that those who can afford to leave are increasingly doing so. Yet the long-term effects of climate change are themselves the most severe. A 2018 study pegged annual GDP growth in India at 6.4 percentage points if Earth’s temperature rises by 2 degrees Celsius, the worst in the world after countries in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Is.

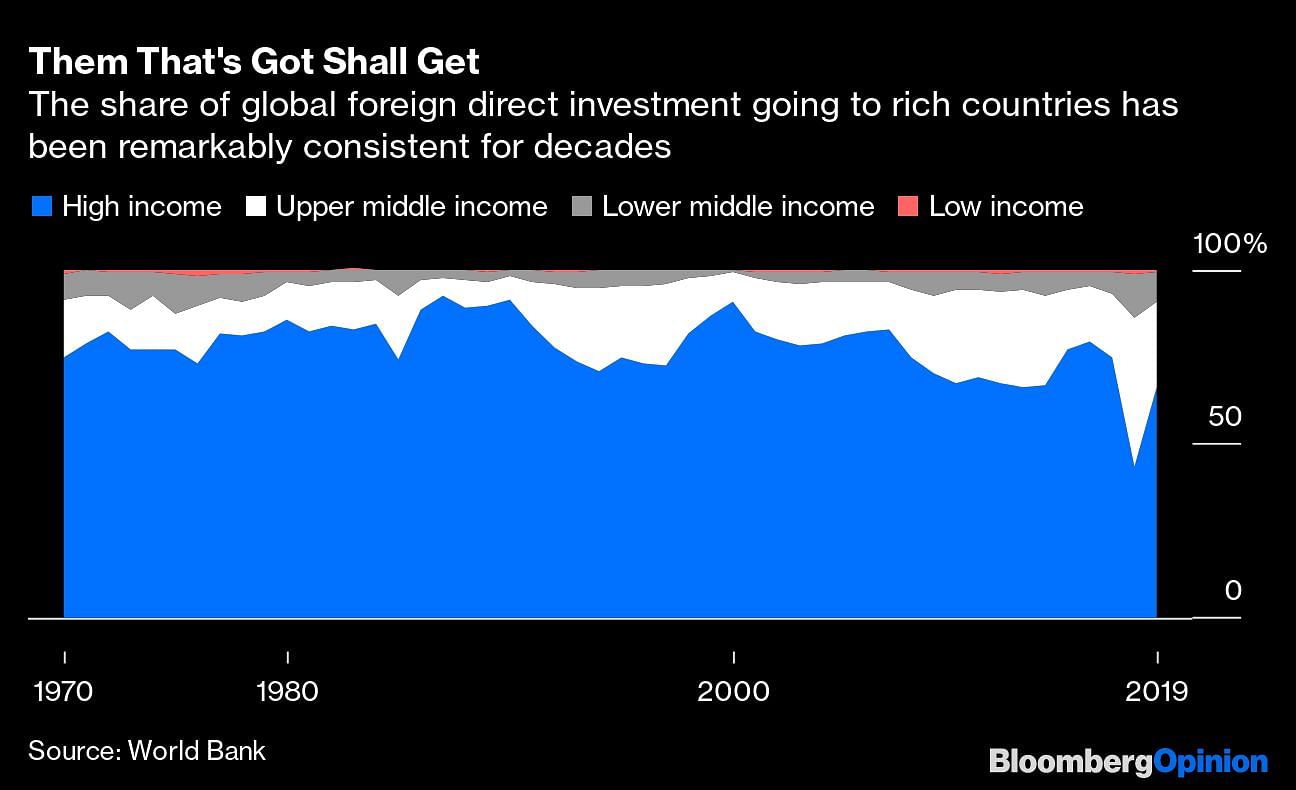

Rich countries should not take this as a reason to avoid their own difficult choices. As much as developing economies seek to decarbonize, they still lag behind low availability of cash to build new power plants. Most of the cost of running a fossil-fired generator is spent buying fuel during its operating life, but for wind or solar almost all that expense comes at the manufacturing stage. This confers an enduring advantage to coal and gas because prosperous nations have historically been reluctant to offer up-front, long-term loans to emerging markets that need renewable projects.

If financial engineering was progressing at the same pace as mechanical engineering over the past decade, trillions of dollars of investment stuck with diminishing returns in developed markets would be looking for opportunities in areas where electricity consumption is set to increase in the coming decades. . Unfortunately, the backlash on that front still continues. A blueprint for a $100 billion annual climate fund for emerging economies released this week still fell short of the amount first pledged at the 2009 Copenhagen climate conference.

The challenge for both sides is to look beyond their past and glimpse the opportunity ahead. India has the lowest rate of emissions per capita of any major economy. Now it has a chance to do something no comparable country has been able to achieve before: prosper by using cheap, green power that didn’t exist until a few years ago, instead of protecting its citizens’ health and deteriorating environment. at cost.

What emerging economies do now on energy transition should be measured not by the small scale of their historical flaw, but by the vast scale of their future opportunities. Indira Gandhi warned of a developing world polluted by its poverty. There is an even greater risk that instead nations will become poorer from their pollution. –bloomberg

Read also: The Indian economy is showing more signs of recovery as the festive season begins

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay a price to maintain this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.