Veteran photographer Sunil Gupta looks back on how cameras shaped his life, outlook and identity as a gay man in the 1970s

Veteran photographer Sunil Gupta looks back on how cameras shaped his life, outlook and identity as a gay man in the 1970s

What does it mean to be a gay Indian? 69 years old photographer, artist and activist Sunil Gupta is yet to get a reply. “Or, it changes all the time,” he says.

When Sunil left Delhi at the age of 15 to emigrate with his family to Canada, his Indian past rose to obscurity. It was Montreal’s gay liberation movement of the 1970s, and his discovery of the word ‘gay’ drew him closer to his identity. The camera played the role of a catalyst in this journey of self-discovery.

Documenting the movement, marching in the streets, with camera in hand, he paved the way for his own sexual awakening. Today, after decades of asking questions, learning, learning and evolving silently with his camera, living with HIV, Sunil boasts a significant body of work that reflects life, and should be. He was recently in Chennai for a discussion titled Sunil Gupta: Practicing for a Life in association with the Chennai Photo Biennale and the British Council of India.

Sunil first took an old analog German camera in the 1950s. To capture the sisters of their childhood friend, who happily posed as models, like they would for a magazine shoot. Soon after, he suddenly moved to Canada. Cinema at that time was both a relief and an education for him.

One of Sunil’s initial clicks. photo credit: Sunil Gupta

But enamored of the freedom it gives, he turned to the camera. “I bought a film camera as a student, and started shooting .. mainly family. Then I became involved with the gay liberation movement at my university and created a tabloid for which I began to teach myself photography. Too Not good pictures… I was just trying to document what was happening,” he says.

Look back

His collection, Friends and Lovers: Coming Out in 1970s Montreal, is a welcome collage of happy memories—of a carefree life painted with renewed hope and liberation. A black-and-white frame shows three friends preparing to break into a dance on the streets of Montreal, who are delighted to have found their tribe.

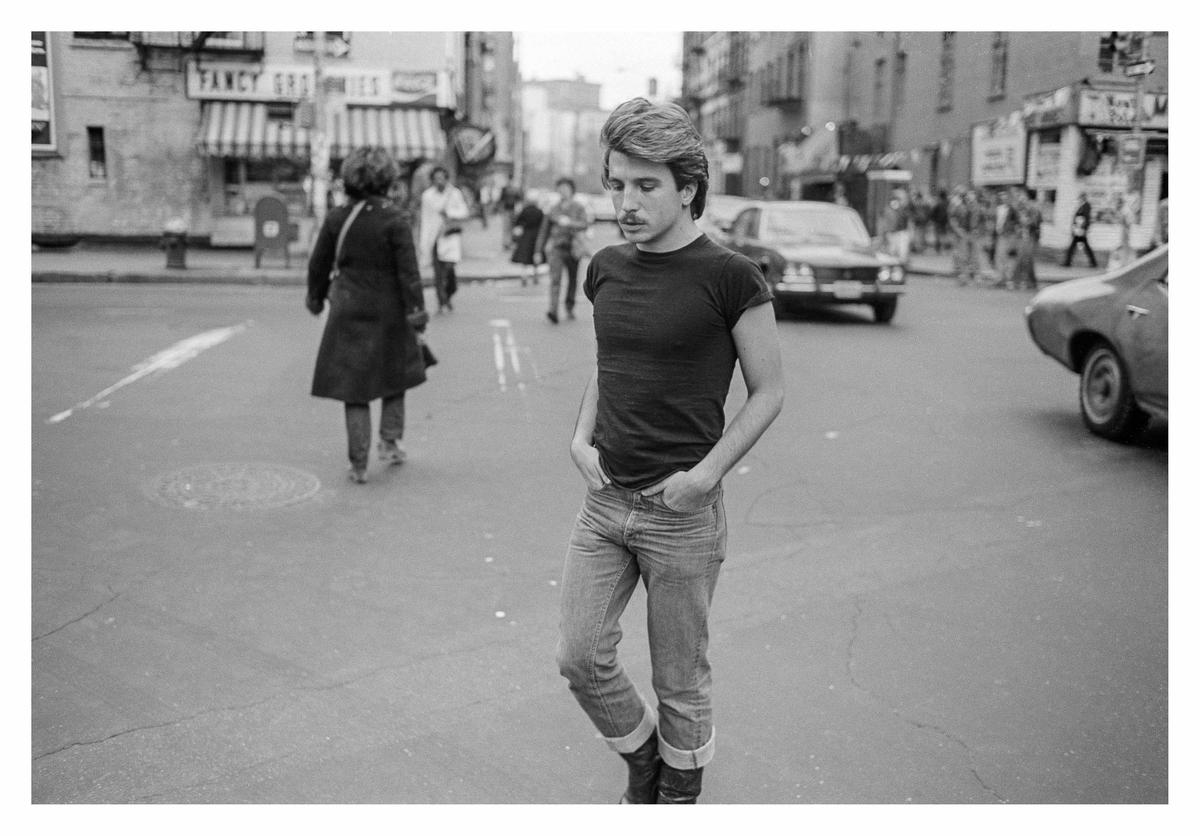

Another important moment in his personal history is in New York where he documented a thriving “gay public space like it had never really been seen before”. He originally went on to enroll in an MBA program, but ended up learning photography with Lysette Models, whom Sunil calls his mentor, at The New School, New York. “He pushed me into photography and I listened to him.” He remembers the days before the AIDS epidemic when everyone was young, busy and affluent. Christopher Street, New York 1976, was a series that grew out of weekends spent “cruising with a camera”. It captures the city, its streets and people, characterized by infectious, youthful energy.

A fascinating image from the series The New Pre-Raphaelites | photo credit: Sunil Gupta

Sunil breaks the flow, saying that cruising (to get out of his house and meet others) was something gay men used to do everywhere in the world. “Today it has been replaced by the Internet, which has had very disruptive consequences,” he is of the opinion.

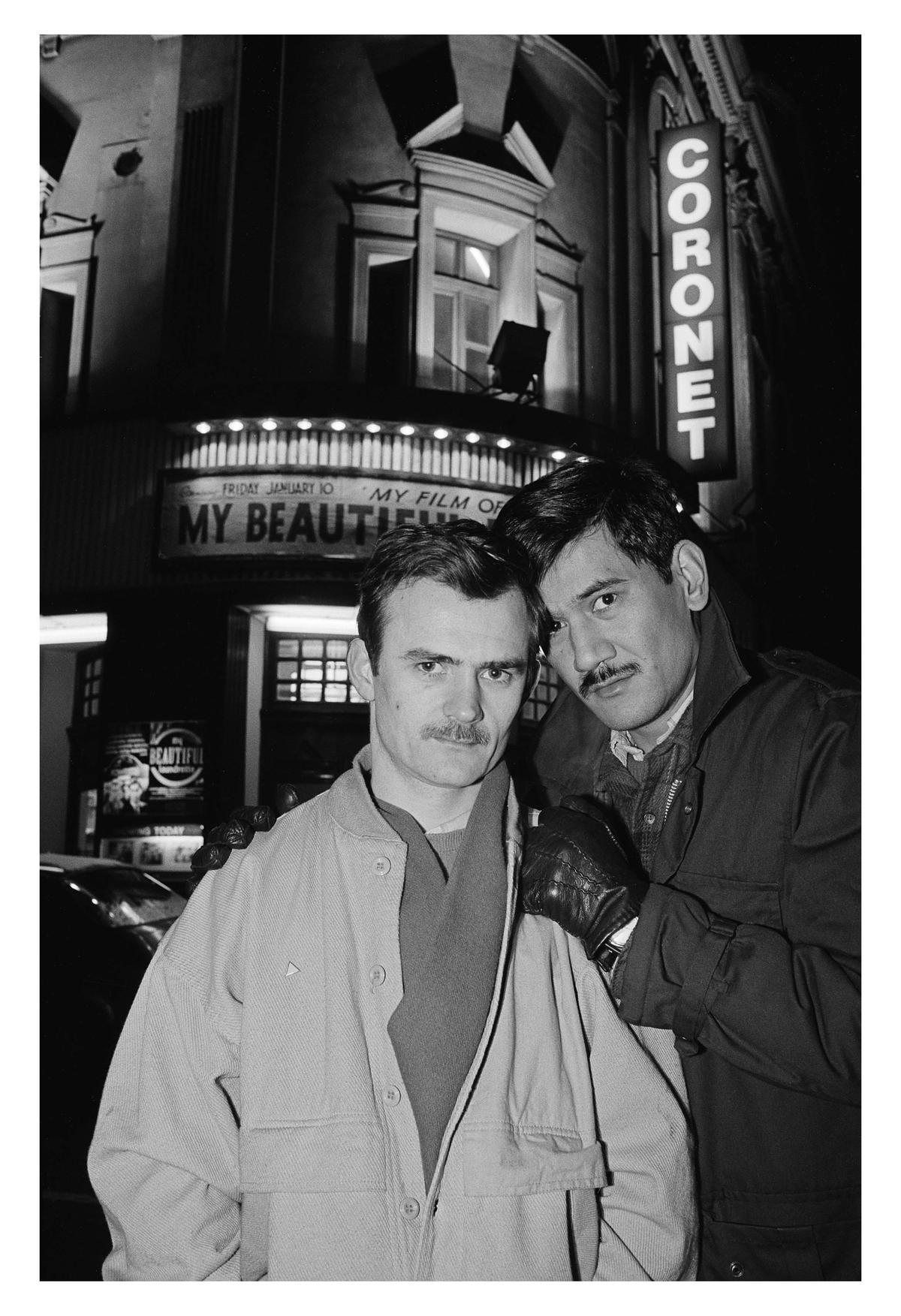

In the early 1980s, after graduating from the Royal College of Arts, he landed in London, a post-colonial world “where everyone was reading Homi Baba and Gayatri Spivak”. Aesthetically, it was a postmodern world, he remembers. “I wanted to get back to my Indian roots seeing the Indian interest in popular culture here.” This was also the time when he discovered homosexual culture in India, which had its own language. However, in the ’80s, Sunil says his central passion was focused on race and representation. To lobby Indian and African photographers who found it difficult to show their work, he, along with his peers, founded Autograph, which still exists today.

keeping it real

Raising socially relevant issues for decades is no trivial task. What makes photography the perfect medium to show these realities? “mainly because it’s a representational medium that surpasses any prior knowledge you need to decode it [the image]He points to an example: “My formative decade after college was around racial identity. And I think self-photography was the best medium for this because a picture very clearly describes it. Is.”

From the series titled Christopher Street, New York 1976 | photo credit: Sunil Gupta

However over time, both Sunil’s practice and the issues he addresses have evolved. “Initially, I looked at them in a very simple way. I was modeling myself in the photography style of the 1950s to take a more humanistic, social change-approach.” However, in the ’80s, when he received his art education, and traveled to India and institutionalized poverty As he took a closer look at social issues, he began to question the purpose of social documentary and the risk of it being voyeuristic. “As an exercise, it became untenable.” His perspective changed as well. Today, he Admits to still learning and not learning about the issues he talks about.

From Delhi to Montreal to New York, back to Delhi and London (which is now the home base), Sunil’s cameras have captured the realities of the LGBTQIA+ movement in cities and countries. He does not believe in the concept of a permanent home. He says, “In short, home is in my head. It’s not a physical place. It travels with me. It’s in human relationships that I’ve been nurturing over the years.”

From a series of photographs capturing aspects of the black experience in London | photo credit: Sunil Gupta