RRajasthan, for more than a generation, has been a part of the infamous acronym Bimaru. There have been dire indicators of this in health, education and economic consequences. However, in recent years, the state has pulled itself away from its lower-tier counterparts to become a medium state. It has performed better in terms of improving the health and educational status of its citizens than Uttar Pradesh over the past few decades.

It is common these days that the chief ministers of different states are campaigning for their party in different poll-bound states. Let us hope that in the upcoming elections in Rajasthan, it is not the CMs of Uttar Pradesh (Yogi Adityanath) and Madhya Pradesh (Shivraj Singh Chouhan) who will come to Rajasthan to describe the state as their own. Instead, it is expected that the chief ministers of Maharashtra and Punjab will do so.

Read also: Long, unbroken chief ministerial tenures are not good for democracy. See example of Odisha, MP

vicissitudes

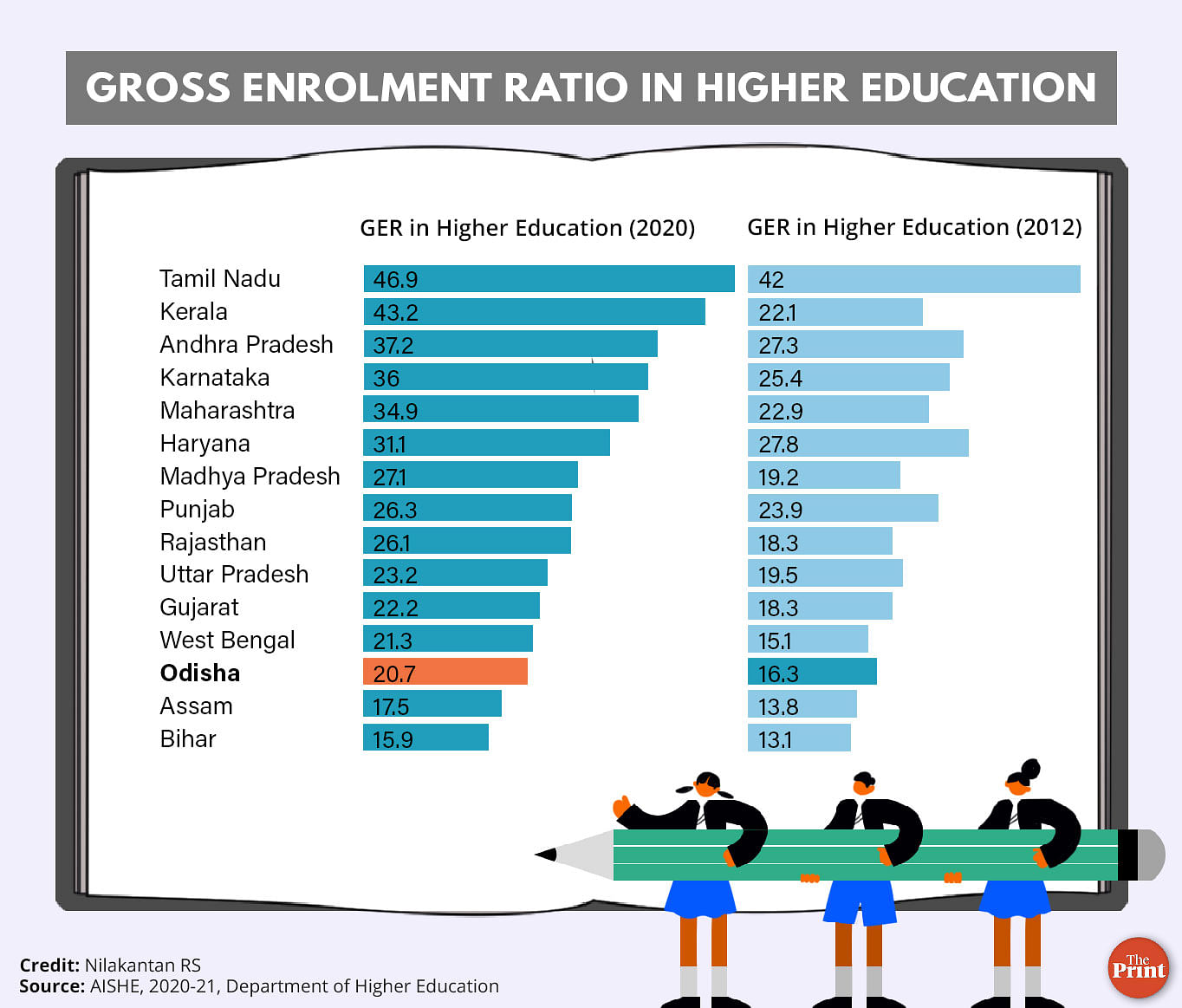

The infant mortality rate in Rajasthan at the beginning of the century was 81. Its Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) in higher education in 2012 was 18.3. Both are much worse than the national average. More importantly, these indicators were in line with other states – Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar – that complete the BIMARU acronym.

Rajasthan now has a GER of 26.1 in higher education, which is also the national average. Similarly, its IMR in 2020 was 32, which is again close to the national average.

Graphic: Manisha Yadav | impression

A useful benchmark state for Rajasthan is Uttar Pradesh. This has also happened in the backdrop of much noise on open facilities and governance model. Although both the states still have a lot of work to do, Rajasthan is slightly better positioned in terms of its ability to meet these challenges.

While politicians make a lot of noise about free facilities depending on where they sit, Rajasthan has been accused of digging that in the recent past, a simple truth is that the budgetary allocations for the core sectors of health and education are limited to the citizens. is a necessary condition for the improvement of life. , The question is, did Rajasthan achieve slightly better results than Uttar Pradesh because it made slightly better allocations to the core areas of health and education?

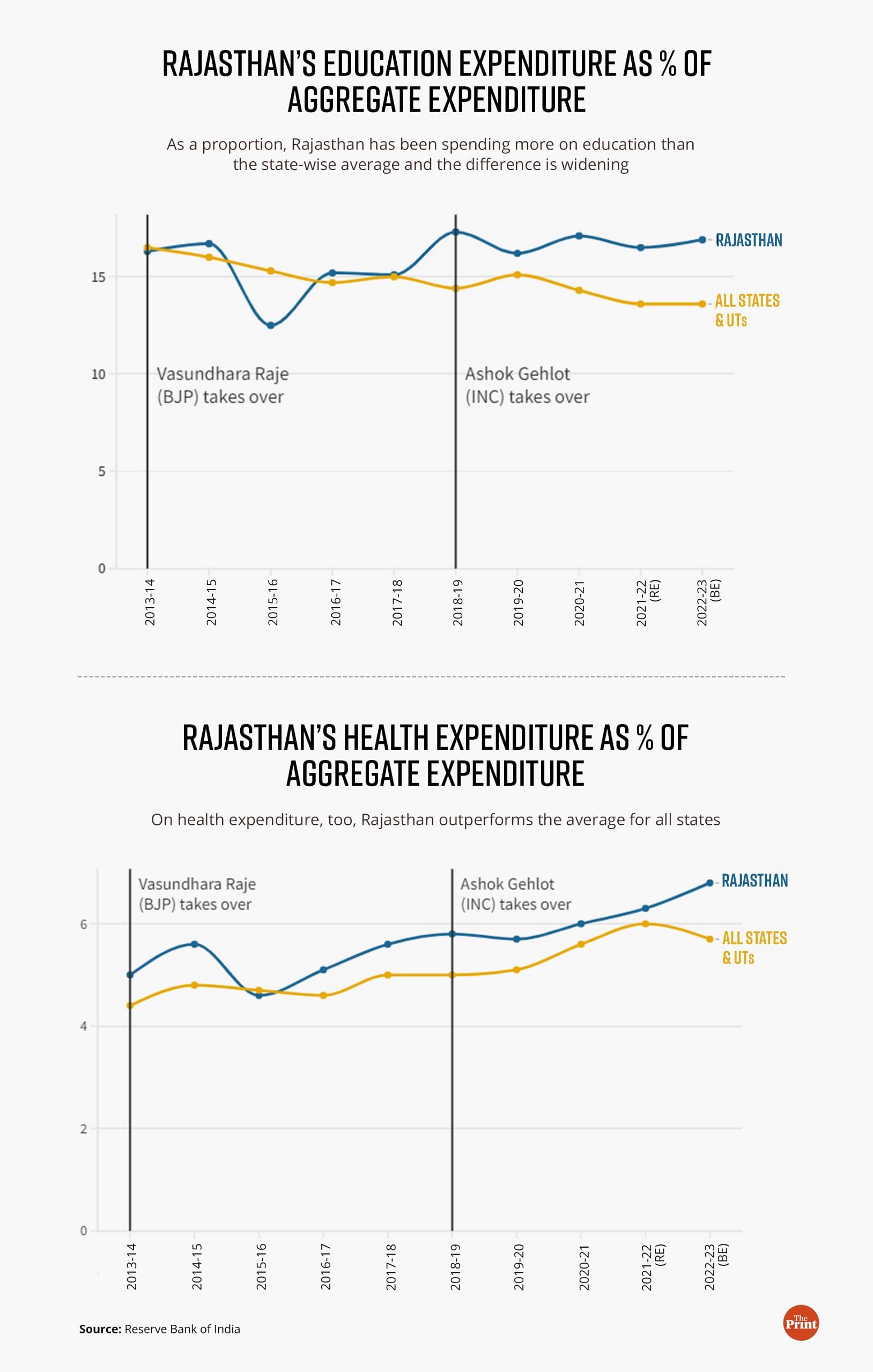

A glance at the budget documents of these states for 2023-24 tells us a lot. Rajasthan’s expenditure on education is estimated at 19.5 percent of its total expenditure, while Uttar Pradesh’s expenditure is estimated at 13 percent. A useful benchmark here is the national average of 14.8 per cent. Both of these states have historically had very poor results in education. So, a reasonable expectation would be that these two states spend more than the national average. After all that’s why we elect governments – to make these spending choices on our behalf. Its implementation is, in principle, left to an apolitical bureaucracy.

Rajasthan seems to have made a choice that most people would accept. While Uttar Pradesh has to answer some questions.

And it is not that Rajasthan, as a proportion of its total expenditure, has spent more on education than the national average. This has been a feature of the state budget for many years. And the benefit of that political decision is that Rajasthan, which a decade ago performed worse than Uttar Pradesh in the field of education, now has a higher GER.

Read also: There has been a surprising decline in the economy of West Bengal. very passionate about farming

keep finances intact

The story is pretty similar in health spending and outcomes. For the last decade, except for one year, Rajasthan has spent more than the national average of its total expenditure on health. As a result, the most important indicator of health – IMR – has improved exponentially compared to its peers. Rajasthan has improved the most among BIMARU states, improving its IMR by 60 per cent in the last two decades. It still has poor health indicators, but they are no longer as shockingly bad as Madhya Pradesh or Uttar Pradesh.

The financial condition of the state has also not derailed due to these reforms due to higher expenditure in health and education. They have brought in relatively stable, albeit slightly above average, fiscal deficits. It is expected of a poor state – after all we want that state to be in deficit to improve human development indicators so that those citizens become productive in future and eliminate the deficit in the process. This is the virtuous cycle that democracy seeks.

Neelakantan RS is a data scientist and author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Thoughts are personal.

(Editing by Anurag Choubey)