MAt Vani Varta and the Indian Paper Currency Museum in Bengaluru, it tells the story of long-gone kingdoms and divided nations. The currency notes have been painstakingly collected for over 50 years by businessman Rezwan Razak, co-founder and joint managing director of Prestige Group, a real estate company.

Razak has turned the fruit of his life-long passion into a private museum open to the public – which has now made him one of the world’s largest collectors of Indian paper currency notes. Two years ago, he unveiled South India’s first currency museum, the ‘Rezwan Razak Museum of Indian Paper Money’.

The museum, which resembles a luxury showroom, houses the country’s wealth—currency notes of all shapes, sizes and colours. Some of the notes displayed are from ‘Bank of Hindostan’, ‘Bank of Madras’, ‘Bank of Bengal at Lahore’ and other pre-colonial era institutions. But the nearly 700 unique notes represent only 6 to 7 per cent of his collection.

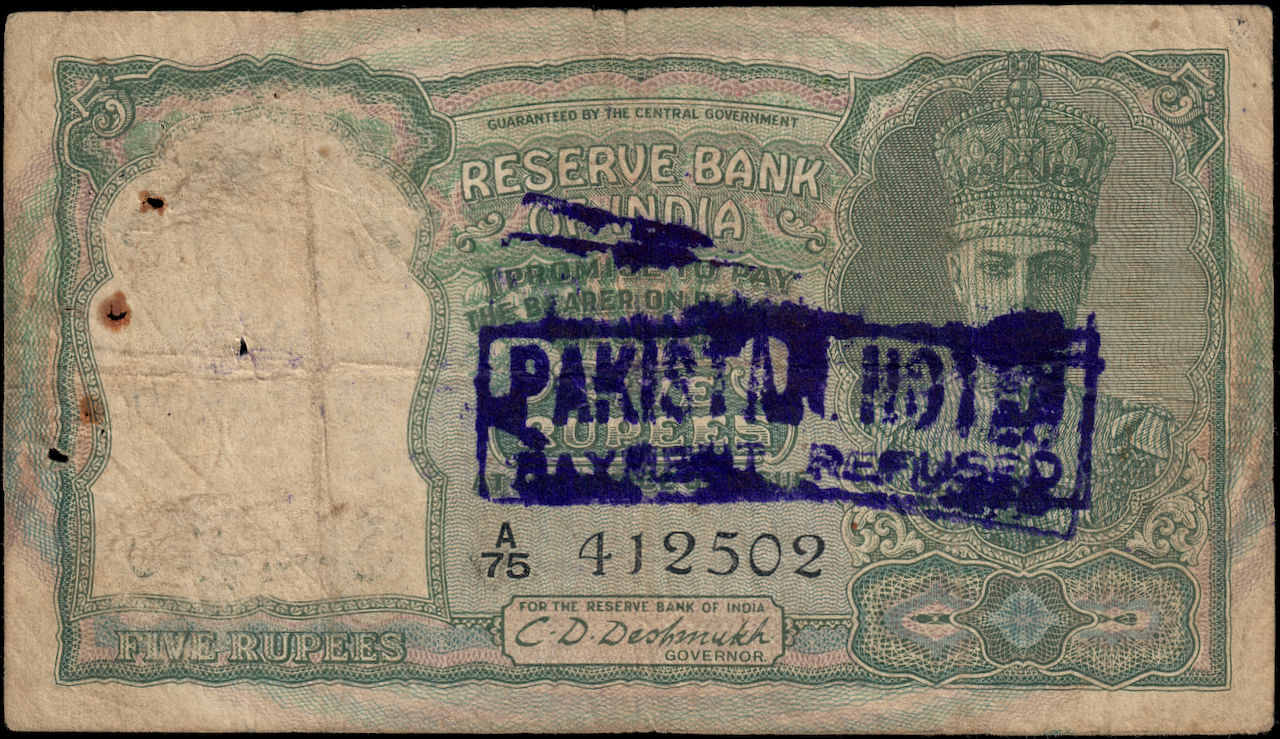

Payment Declined

Rezwan Razak was 12 years old when he first found a box of notes in his grandfather’s safe. It was a note from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), on which was written ‘Pakistan, refusal to pay the note’. He didn’t know anyone who had the answers and the internet was still a few decades away.

“Pakistan and India had the same currency, and when partition happened, they (Pakistan) did not have their own money. Therefore, he overprinted the notes with Government of Pakistan in English and Hukumat-e-Pakistan in Urdu. They (Pakistan) started their life with this money,” Razak said over a phone call.

Refugees who came to India from Pakistan carried these notes with them in the hope that it would help them start a new life. But on arrival, they found that most of this currency was not legal tender in India.

The bankers then stamped the notes to ensure that they were not re-circulated. Although the notes were demonetised, one of them set Razak on the quest of a lifetime.

Crowds are rare at the Razak Museum, but it does attract the occasional curious visitor.

“It’s a huge collection, very well curated. I didn’t expect the history and development of paper currency to be so interesting, but it’s such a testament to the period that I walked away feeling completely fascinated ,” says Atula Krishnamurthy, a technology lawyer.

Razak says he still has “ItchingOr itching to collect more notes. For the past 15 years, he devotes a few hours every day to tracking down forgotten notes for his collection.

Read also: 2020 was a do or die moment for museums. but now there’s a new divide

half note

The museum is located inside a commercial building on Brunton Road in the commercial district of Bengaluru, which is also the head office of the Prestige Group.

At the entrance, a showcase displays the ‘Evolution of Indian Money’ with shells found in the oceans, which were in use in 1500 BC. It then moves on to the ‘punch-mark coins’ of the periods of the Mahajanapadas, the Keshavas, the Guptas and the Mughals. They are followed by the currency used during the British rule, and finally, there is the digital currency which is just a smartphone on display.

The walls display early banknotes from the Presidency and private banks between 1770-1861.

The notes are sometimes accompanied by anecdotes and vignettes. A note on the wall of the museum reads: “For security reasons the notes were cut in half and sent by post and on acknowledgment of receipt, the other half was also sent by post. The two are then clubbed together and sent for encashment.

two annas eight rupees

The demonetisation of 2016 was not the first in Indian history. In 1946, Rs 1,000 and Rs 10,000 notes were withdrawn from circulation. Today, they have found a place in Razak’s museum.

Until 1929, most of India’s currency was printed outside the country by the Bank of England. The establishment of a currency note press at Nashik in 1928 marked the beginning of a new chapter in India’s currency printing history, however, at that time the face of King George V was still inscribed on the notes.

But a newly independent India created its own design incorporating elephant, deer and then tiger.

“Symbols had to be chosen for independent India. Initially it was felt that the portrait of the king should be replaced by that of Mahatma Gandhi. The designs were made for this. In the final analysis, it was agreed upon to select the Lion Capital at Sarnath in lieu of the Gandhi portrait,” according to information received from the RBI Museum. Website.

Read also: I ate non-vegetarian Harappan food and did not eat beef with it

There is a note of ‘two annas eight’, which was withdrawn from circulation as it was not a popular denomination, reflecting the experiments carried out at the time.

Although most of these anecdotes and historical records are explained on the many boards along the walls, the keepers of the museum are equally knowledgeable.

Razak’s collection is so vast that he has arranged notes bearing the birthdays of Indian prime ministers. “We can do the same with the Presidents of India,” the caretaker tells a senior citizen taking a tour of the facility.

There is a partially torn note found in 1917 from the SS Camberwell ship near the Isle of Wight on its way from London to India and taken from a 1983 James Bond film. octopusIn which Kabir Bedi is.

An entire wall displays the latest currency notes that are in use today, from the bright yellow Rs 10 to the bright yellow Rs 20, and the fuchsia pink Rs 2,000, reminiscent of the really special old paper currency.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)