Photographs published on LIFE Magazine dated February 16, 1948

| Photo Credit: special arrangement

On the walls of the Asian College of Journalism today is art that begs a second glance. At first, it may seem amateur-ish. But a closer look reveals layers — of resistance, activism and opinions that defy fear. Superimposed on unassuming hessian sheets are words and images of over 280 writers, artists and activists, each driving home the importance of unity and defiance.

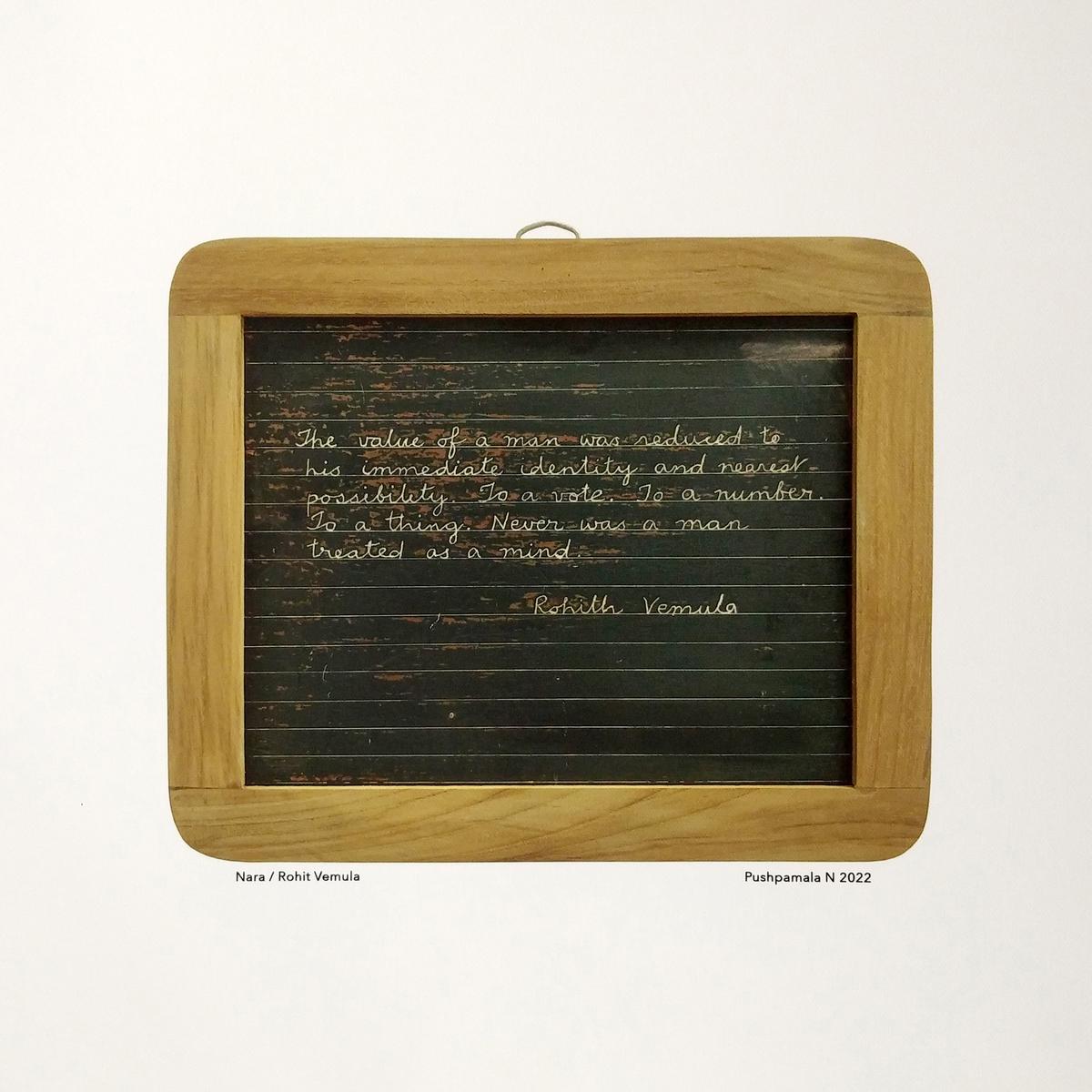

Take for instance, artist Pushpamala N’s image of a writing slate that carries an ode to Rohith Vemula or photojournalist Pablo Bartholomew’s photographs of 1970s Bombay where late thespian Gurcharan Singh Channi performed his radical street theatre production Disturbed Area, that spoke of State violence and political conflict. Titled Hum Sab Sahmat, a pandemic project, the display pays tribute to SAHMAT’s (Safdar Hashmi Memorial Art Trust) 1991 exhibition titled Images and Words where artists were encouraged to react to the political climate of the time, using any medium

An artwork by Gargi Raina

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

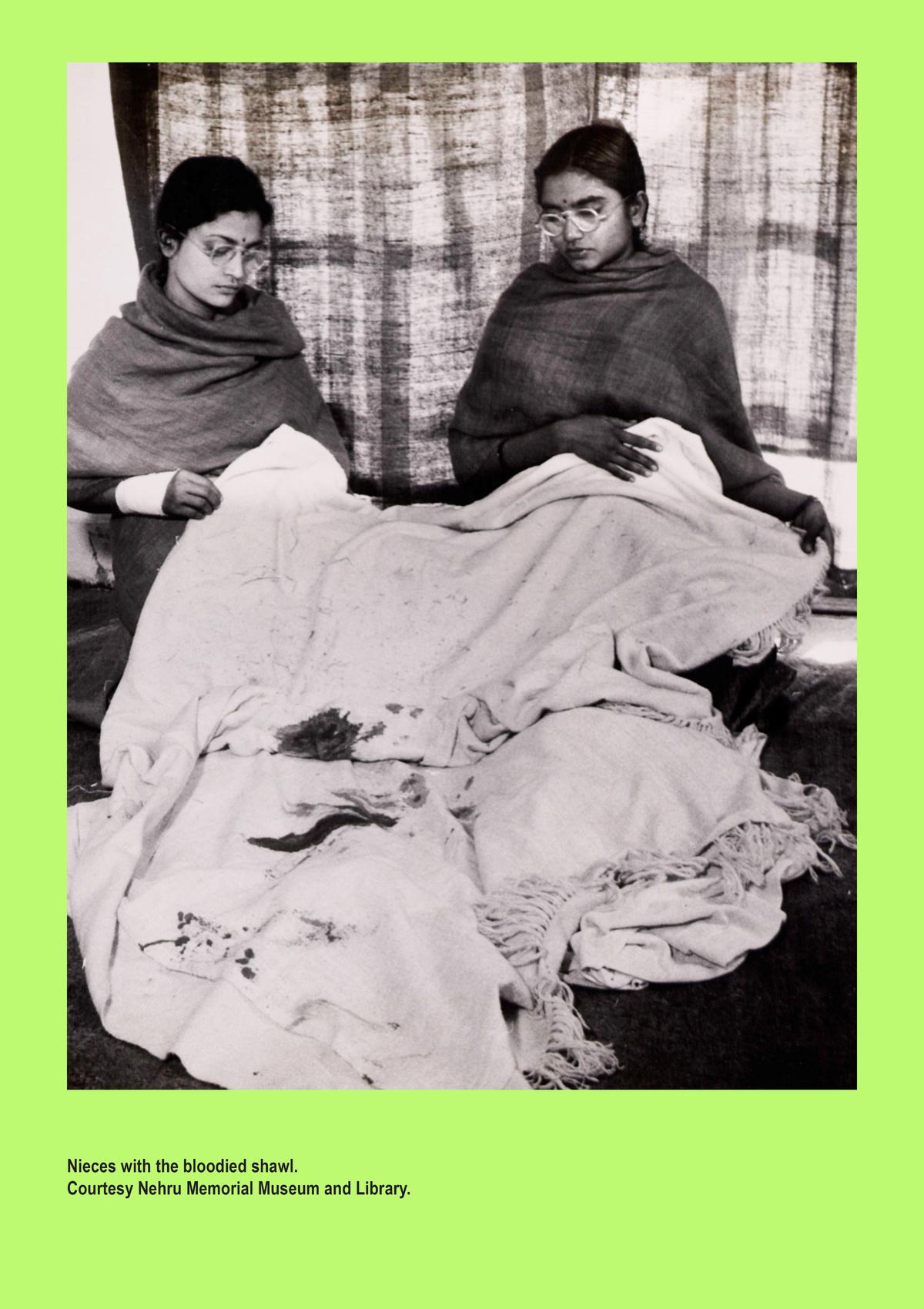

Curated by Ram Rahman and Saarthak Singh, an allied fascinating exhibit of photographs by Henri-Cartier Bresson, Margaret Bourke-White and Max Desfor titled The Light Has Gone Out, conceptualised last year, takes us through the moment and aftermath of Gandhi’s assassination. It is a study on how photojournalism proves pivotal in shaping a nation’s history.

Ram who is also one of the founders of SAHMAT says, “Some of these images have never been seen before. The idea was to bring out this moment in our history, particularly at this point in time. It was also to remind people why Gandhi was killed and who killed him. The photographs show how personal stories and practices perfected the way the event got documented and reached the public booth.”

More to come

Last weekend saw a captivating, and almost conversational performance by Gaana Vimala, who belted out many Ambedkar anthems written by herself, followed by two Tamil plays, Idam and Mei directed by artist and activist Pralayan. In tandem with the exhibits on display, a line-up of performances await:

On March 22, 5.30pm onwards: Performance as Politics: Song and Dance by Nrithya Pillai, vocal and nattuvangam: Janani Ramesh; flute: Devaraj; mridangam: Ganesan, followed by Dafs Musical Concert by Muslim Fakirs

On April 5, 5.30pm onwards: Chennai Kalai Kuzhu will present King Mahendravarma Pallavan’s Mathavilasa Prahasanam, dramatised and directed by Pralayan

Nieces with the bloodied shawl

| Photo Credit:

courtesy Nehru Memorial Museum and Library

Spread across the corridors and on wooden structures erected at the entrance, are messages that touch upon political developments in the country, timed around the pandemic. Which is why artist Aban Raza, whose team curated the display, envisions it as a continuing project. “The first action was to segregate the reponse theme-wise. Some were talking about the environment, some about the rise of communalism, while others were commenting on women’s rights and the attack on universities and on the Delhi riots. It was a lot of working on one image with a text to make sense of the narrative.”

The format, which is unaffected by the space of display, was designed with accessibility at its centre. The show has travelled to Shantiniketan, Bhopal, Ajmer, Jaipur, Himachal Pradesh and protest sites since its inception.

Aban says, “The idea was to talk about where India is heading, and perhaps not agreeing with the direction it’s heading. It was a deliberate decision to involve writers, artists, photographers, journalists …” On each sheet is Hum Sab Sahmat written in multiple languages, signalling the multicultural nature of the opinions.

Pushpamala N’s artwork

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

The picture of Gandhi’s cremation shot from above is a fascinating one for many reasons, says Ram. “The story is that Cartier-Bresson used his small Lyca camera to move around and take some pictures and when he couldn’t get up on the machan (platform), Max Desfor, offered to take some pictures on Cartier-Bresson’s camera.” Two weeks later, one of those pictures appeared in LIFE magazine with an attribution to Cartier-Bresson. “I found that fascinating, how do you then credit an image is the question.” The picture of a young Gopalkrishna Gandhi by the funeral pyre was one of the other rare finds, a picture that Ram did not know the existence of.

He concludes, “A lot of these images bring alive a history that you have known. But a visual record of it somehow makes it more tangible and closer home.”