A still from Catapults to Cameras

It’s a sultry afternoon. Five children are idling on a bridge amidst lush green fields in an obscure village in Jhargram district, West Bengal. They are playing with a catapult, trying to improve their aim to strike their target — a bird.

This scene comes early on in Ashwika Kapur’s film Catapults to Cameras. Cut to the end: one of the children, Ajay, hands his catapult to Kapur, who is heading back home to Kolkata after an adventurous week with the young boys. Ajay now holds a camera in his hand.

Catapults to Cameras is a poignant story of transformation. The five boys — Raja Khisku, Ajay Mandi, Surajit Tudu, Tarash Mandi and Lalu Soren — go from being future hunters to conservators. Produced by RoundGlass Sustain, it is directed by Ashwika Kapur. The short film was shortlisted in the ‘Impact Campaign’ category in the prestigious Jackson Wild Media Awards 2024.

Ending the killing spree

It’s difficult to fathom that in our country, where hunting is illegal, there are ritual hunting festivals. In several villages in southern West Bengal, hundreds of men and young boys participate in an annual bloodbath. Carrying traditional weapons such as axes, spears, catapults and bows and arrows, they arrive in trucks, cars and on motorcycles, and kill everything that moves — birds, wild cats, boars, snakes, reptiles and even tigers, if they can find them.

Kapur was disturbed when she learned of them while volunteering with HEAL (Human & Environment Alliance League), an NGO that works in the field of wildlife conservation. She and a few members of HEAL discreetly recorded one of the festivals, and some of the footage has found its way into the film. It’s gory, to say the least.

But that’s not what Kapur wanted to focus on. “It was never a film; it was an experiment,” says Samreen Farooqui, executive producer. “Working with five children for a week and making it into a film was not fair. We had to stay on. Catapults to Cameras had to have an impact.” The boys had already accompanied their fathers on hunts, and one day, would have participated in the festivals. Kapur and RoundGlass Sustain believed that by impacting the children’s conscience, they could break the chain.

Merely a sport

HEAL has been documenting, monitoring and investigating ritual hunting in West Bengal’s southern region. According to Meghna Banerjee, lawyer, environmental activist and CEO of HEAL, human-animal conflict in the area is enormous. It will require many such interventions to change the mindset. While the hunts are mistakenly assumed to be rooted in traditional tribal culture, Banerjee states that “there is no cultural significance. If you ask them why they kill, they don’t have an answer”. Moreover, some who participate do not belong to any of the tribes. “These men come in cars from different areas. It happens on 50 separate dates throughout the year, so you can imagine the scale. They are drunk and kill everything, including jackals and wolves. So it’s not just for meat,” she adds.

Influencing change

Early last year, accompanied by Kapur and HEAL’s co-founder Suvrajyoti Chatterjee, the young boys were taken on field trips where they took photos of animals, birds and reptiles. The pictures were then exhibited in the village. “Some of the photographs were amazing. Our approach was that under no circumstances were we going to preach. We were not there to chastise them,” says Kapur, who won the Wildscreen Panda Award in 2014 for her documentary, Sirocco: How a Dud Became a Stud, on a kakapo, a critically endangered parrot native to New Zealand.

Ashwika Kapur with the boys at the workshop

During the week, the children encountered a snake rescue mission and even witnessed a dangerous face-off between elephants and villagers. “I didn’t realise the empathy the project evoked in them until Ajay came to me and handed over his catapult. When we exhibited the pictures, the entire community felt a sense of pride.”

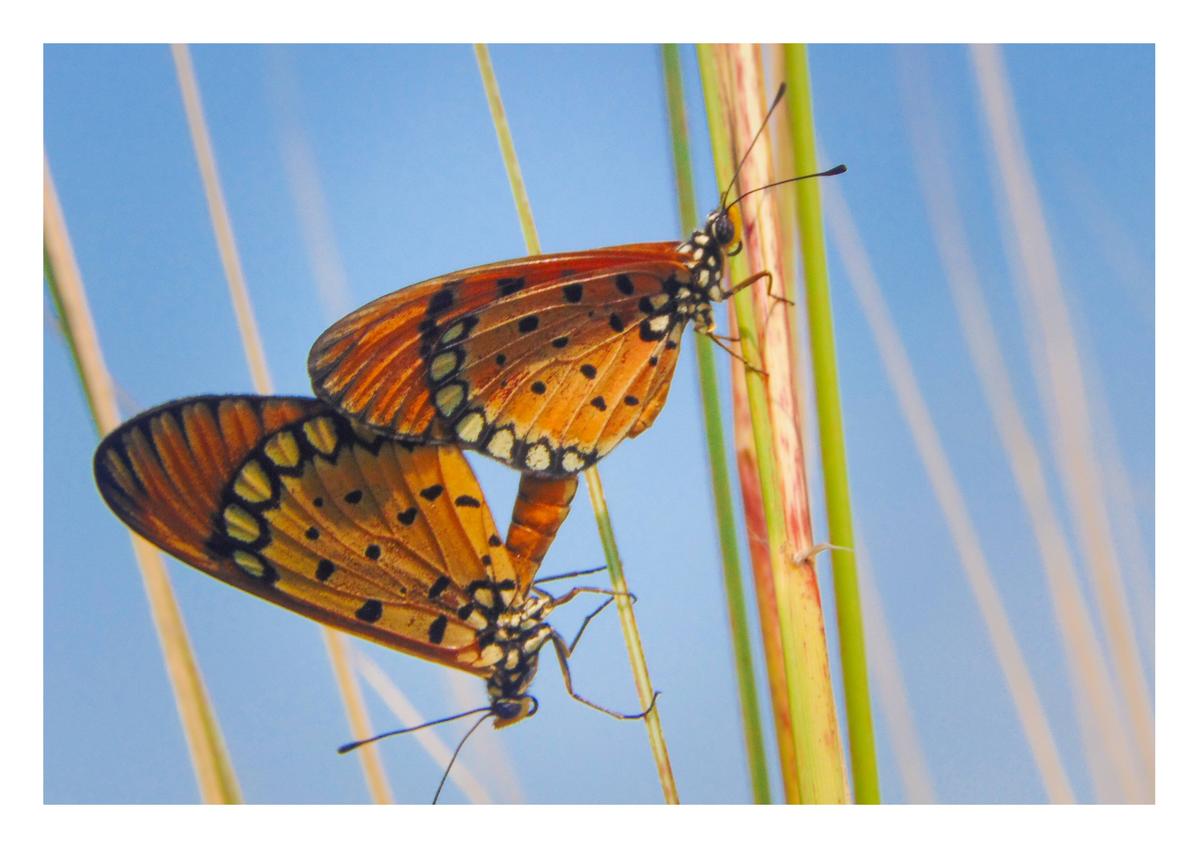

A photo of butterflies by Raja Khisku

Tarash Mandi photographs a monitor lizard

Kapur feels that as “more children go through these workshops, they will become something like local influencers. They will start redefining what is cool, because the scale of this hunt is being driven by the youth”. For now, the five boys have turned mentors for another batch of children — becoming a classic example of the butterfly effect.

The Bengaluru-based journalist writes on art, culture, health and social welfare.

Published – September 12, 2024 01:12 pm IST